AN ENGLISH CUBIST

WILLIAM ROBERTS:

In Defence of English Cubists

In Defence of English Cubists was first published as a pamphlet in February 1974; the Postscript followed in April 1974. The present texts are those reprinted, with the final addition, in Five Posthumous Essays and Other Writings (Valencia, 1990). © The Estate of John David Roberts.

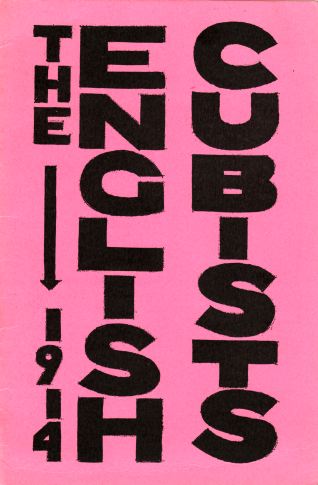

The front cover of In Defence of English Cubists

There are rumours floating around, that we are soon to have another show of Vorticism; and that it is intended to coincide with the publication of a book upon the same subject. If this is so I feel there will be a need to restate my attitude to Vorticism.

In 1956 – forty years after the 1915 Doré Gallery show – Wyndham Lewis had a One-Man exhibition at the Tate, to which were added in a side room, a few samples of the work of those artists, who had participated in the original Doré show, and of some who had not; these artists were labelled 'Other Vorticists'. This arrangement was odd, because in the introduction to the catalogue of his exhibition, Lewis wrote 'Vorticism, in fact, was what I, personally, did and said at a certain period.'

If this was so, it is hard to understand how these other Cubists came to be classed as Vorticist, unless it was to give Lewis added importance. In 1915 the work of these artists ranked in no way inferior to Lewis's. In 1915, it would have been absurd, to have called painters like Nevinson, Bomberg, and Etchells, 'Other Vorticists'. In 1915 Lewis was anxious to form what he called a Platform, for himself. As he once explained to me, 'It is more difficult for an artist, working in isolation (a Painter of Abstracts, that is to say) to impress the public, than it would be if he were a member of a Group' (with a good slogan like Vorticism, no doubt). But at the Tate in 1956, he felt, quite rightly, that he had no need of a group, and could dispense with the planks of the old 'Platform' so helpful in 1915. It seemed however that the organisers of his Tate show had other ideas, and considered that the 'Platform' could still be of use. So we get, in a room adjoining the main exhibition, some minor examples of the work of the 1915 Cubists, with the title 'Other Vorticists.' It is easy to understand, how Lewis, presenting this large collection of his pictures to public view, and supported by his literary reputation, could be made to appear the 'Leader'.

Art critics and Curators, whose chief occupation is writing, find a helpful source for their comments and criticism in the prose compositions of the painter-writer, and show more interest in the pompous statement of aims in the artist's introduction to his catalogue, than to his pictures on the walls. One can guess what an impression this passage from Lewis's introduction to his 1956 catalogue, would have on the Art critics, – 'AS REGARDS VISUAL VORTICISM IT WAS DOGMATICALLY ANTI-REAL. IT WAS MY ULTIMATE AIM TO EXCLUDE FROM PAINTING THE EVERYDAY REAL ALTOGETHER. THE IDEA WAS TO BUILD UP A VISUAL LANGUAGE AS ABSTRACT AS MUSIC.'

If this was the aim, who needs pictures?

Lewis has stated in one of his many articles, that the writer is superior to the artist, because he knows so much more. He refers here no doubt to the Art historians, and the constructors of aesthetic theories.

One can say that Lewis's painting has its origin with the French Cubists; and his manifestos, with the propaganda literature of the Italian Futurists. What Lewis has made of these two influences, he calls Vorticism. With regard to this mystifying catch-word, I agree with Lewis, that it should only be used in reference to his own work; and that the term Cubist should be employed, to describe the abstract painting of his contemporaries of the 1914 period.

It is hard to fathom the reason for this third exhibition of Vorticism; I foresee, that on the strength of the statement: 'Invited to send to the 1915 Vorticist exhibition' printed in the 1956 Tate catalogue, we shall again have Bomberg, Nevinson and McKnight-Kauffer, masquerading as 'Other Vorticists'.

It is instructive to see upon what slight foundation, certain independent Cubists of 1915, became 'Other Vorticists' in 1956. For instance: –

Atkinson, is 'Invited to show with the Vorticists 1915'.

Bomberg, is 'Invited to exhibit at the Vorticist Exhibition 1915'.

Kramer, also 'Invited to show at Vorticist Exhibition'.

Nevinson, too is 'Invited to show at Vorticist Exhibition 1915'.

Dobson, is brought into this group of 'Other Vorticists' on the strength of having made the acquaintance of Lewis sometime about 1920.

I think 'Guest Artists' would better describe these exhibitors at the Doré Gallery show in 1915.

Again, the statement 'Signed the Manifesto', which refers to the List of names printed at the beginning of Blast No. I, is also misleading.

Similar criticisms were made by me in various pamphlets at the time of Lewis's Tate exhibition in 1956. It was only with this event, that I realised what useful propaganda could be made for Lewis, with this slogan 'Vorticism'. As this terse item from the Penguin Dictionary of Art and Artists, compiled by two ex-students of the Courtauld Institute, will show: 'Vorticism. A variety of Cubism, exclusive to England, invented by Wyndham Lewis.'

It is not a question here of what Lewis means by Vorticism, visual or otherwise, but whether he should attribute to the other Cubist painters, his contemporaries, his own ideas. As in the paragraph which heads the 'Other Vorticists' section of his catalogue; where he throws down the Vorticist gauntlet, and writes – 'by Vorticism we mean, Activity as opposed to the tasteful passivity of Picasso'; but to me Picasso's work is neither tasteful or passive, but brutal and explosive; 'tasteful passivity,' would suit better the pictures of Burne-Jones. There follow statements of a similar kind, in this Mini-Manifesto.

It is strange, that most of the abstract paintings of this period have been lost, and yet the manifestos linger on.

I have sometimes been asked for interviews by Art critics, and students with theses to write, who wished to discuss Vorticism with me. However I felt that these enquirers would, by their questions and investigations, only distort and enlarge unnecessarily this subject. I wished to avoid, besides, adding more fuel to this conflagration.

On behalf of the Independent English Cubists of 1914.

ATKINSON

BOMBERG

ETCHELLS

NEVINSON

ROBERTS

WADSWORTH

1st February, 1974

Postscript

My pamphlet 'In Defence of the English Cubists' was written, printed and distributed before the opening of the Arts Council's exhibition 'Vorticism and its Allies'; it cannot be regarded as a criticism of that show. I understand that the aim of the organisers of this latest public presentation of Vorticism is to correct the 'Imbalance' of the 1956 Tate exhibition; and they do this neatly by changing the term 'Other Vorticists' into 'Allies'. However, I should have thought, that the best way to get rid of this 'Imbalance' could be achieved, simply by ceasing to give Vorticist Group shows; or if there must be Vorticism, to concentrate solely upon the work of Wyndham Lewis.

I rather think that Bomberg and the other Cubists, would consider it a high price to pay for a little publicity in 1915, that they should be 40 years afterwards labelled 'Other Vorticists' and again, some 60 years from that date, made to appear in the role of 'Allies'. Surely this is the way legends are made; and legends are apt to expand with time.

Thus in 1974 a new figure joins the Group, a Vorticist photographer bringing a collection of abstract photos called 'Vortographs'. As there seems a desire to increase the Group's membership, as well as 'Allies' why not 'Sympathisers'? We might even have a 'Friends of Vorticism' society, where for a small fee those who wished could become Vorticists.

One gets the impression from a study of the large and weighty catalogue, a square foot in size, crammed with biographical detail and masses of other data, that the Arts Council has endeavoured to make it a complete and final research into the subject of Vorticism – but one must not be too optimistic. Yet while it pretends to correct the misarrangement of the Tate exhibition, nevertheless in the large aggressive layout of its pages, it fixes more firmly the positions that the participating Cubists were forced to accept in 1956. Catalogues are becoming more and more important items in Art exhibitions; these bulky, profusely illustrated volumes are readily bought up by visitors. Then, when the show ends and the pictures are dispersed, the catalogue still remains to serve as a memento or reference book. So, if in twenty years from now you wish to know who was who in Vorticism, it will be the information presented by the compilers of the Arts Council's massive, erudite, expensive catalogue that will inform, or mis-inform you.

Finally, once again, I reject this ambiguous term Vorticism; preferring the word Cubism, as defining more correctly the character of the painting I did in the period 1914–1915.

April 1974 W. R.

The poster of the Hayward Gallery's 1974 exhibition 'Vorticism and Its Allies', featuring Roberts's St George and the Dragon 1915

(In a reply to this pamphlet that appeared in the Evening Standard of 28.3.74, Richard Cork, the organiser of the show 'Vorticism and its Allies' wrote:)

'The works produced by this movement, harsh, aggressive, diagonally explosive and yet defined with a linear rigidity quite opposed to Futurism's blurred multiple imagery, can now be seen to possess an impressive unity of aim – a unity which cannot, despite Roberts's latest plea, be described as Cubist in character . . .

' . . . Roberts's contribution is very impressive and I wish he could have gone to see how his work is presented at the Hayward Gallery before damning my efforts so completely. If he does pay it a visit, I believe he will find that Vorticism can reasonably be seen, not as Lewis's egotistical brainchild, but as an appropriate title for a spirit of energetic renewal which revolutionised the course of English painting and sculpture, before the First World War put a brutal end to all its hopes for an art directly expressive of its own time.'

News | Gallery | Auction results | The artist’s house | Contact

List of works illustrated on the site

Catalogue raisonné:

chronological | alphabetical