AN ENGLISH CUBIST

An Artist's House:

William Roberts and 14 St Mark's Crescent

Text and photographs © Pauline Paucker

Based on a talk given to the William Roberts Society on 29 June 2002

The houses in the Primrose Hill area of London were built as one-family houses for middle-class professionals and well-off tradesmen, but with the coming of the railway they turned into letting-houses of the kind described with such distaste by H. G. Wells, whose aunt ran a lodging-house in Fitzroy Road. The novelist George Gissing sent his most unhappy characters to live here, as a symbol of their failure in life (or, worse, he sent them to Crouch End).

William Roberts was no stranger to London NW1: in 1914 he was living in a room in Chalcot Crescent, and in the twenties, with wife and child, in one room in Albany Street. Sarah Roberts said that their son, John, grew up in Regent's Park: it was their drawing-room.

War is a difficult time for artists – who buys paintings then? – and things had not been at all good for Roberts in the Second World War in Oxford, where he and Sarah had gone after being bombed out of their Haverstock Hill flat. Coming back to London in 1946, all they could afford was one unfurnished room in a letting-house backing on to the Regent's Canal in St Mark's Crescent – a house then occupied by a Dickensian low-life crew.

The rear of 14 St Mark's Crescent (painted grey) as seen from the canal towpath opposite

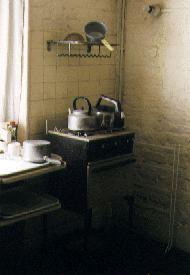

It was the room next to the front door. They had brought their bed, an easel, a small table and two chairs, and an electric hotplate for Sarah to cook on. It was a style of living she was used to – 'That's love among the artists,' she would say

Facilities – that is, lavatory, bath and wash-place – were shared with the basement tenants, a rowdy extended family waiting for the husband and father to serve his time in prison for bigamy. The terrifying mother-in-law of this brood was called Old Mother Dry Rot by Roberts. At one point she had to be bound over at Albany Street police station to keep the peace after attacking Sarah with a soup ladle. The husband or – non-husband – came out of prison, chose this family, and went off with them to Wales. The Robertses took over the vacated rooms.

WR's work was selling again, and he also had a committed patron in Ernest Cooper, who had made money in wartime from his health-food shops. Cooper's wife was a close friend of Sarah's and had presumably influenced him in his choice of artist to patronise. The Robertses could thus rely on a modest income – and their needs were modest.

The official tenant upstairs, who had been subletting, left suddenly with her family and hangers-on. The Robertses were now sole sitting tenants, protected by the then current Rent Act. The owner, wanting to get rid of a troublesome property, offered to sell the house to them for the sum of £1,200 – but this was a sum they had not got. Here a guitarist friend of Sarah's stepped in: Victoria Kingsley, a rentier who lived on inherited capital. Most generously, she offered the money as an outright gift, receiving in exchange some paintings – which proved to be of more value in the long run. But it was a noble gesture.

Now William Roberts had security, no more problems of where to live, and a whole house to cherish. His fellow artists such as Bomberg and Gertler – and Wyndham Lewis – never had such a possibility, having to move from here to there in unsatisfactory accommodation till the end of their lives.

The house first had to be cleaned up – a nasty task – and then WR, the carpenter's son from Hackney, collected his tools and began by making a landing-stage in the garden for his and Sarah's newly acquired wooden rowing-boat. Cameras would be out as they rowed under the Regent's Park bridge.

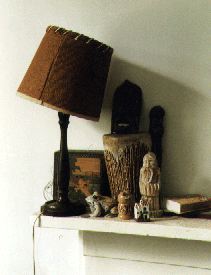

In the house itself he put in a set of doors to screen off the hall. He chose good-quality wood, leaving it unpainted, and devised a system of bars and toggles for closing.

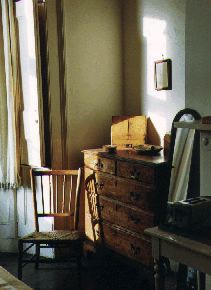

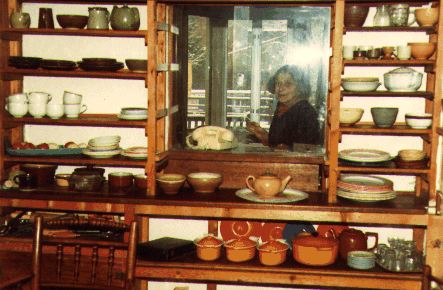

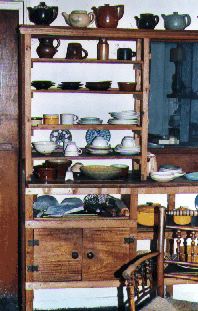

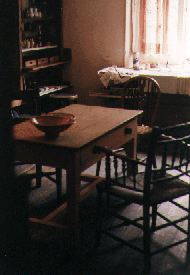

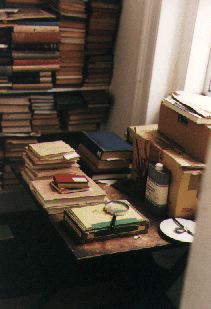

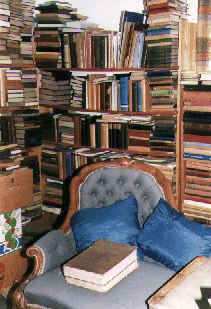

Sarah meanwhile was ripping up the rotting carpets, swearing she would never have any in the house, and prising up the nails – a task of months. The broad floorboards were now revealed, and the treads of the winding stairs. Stripping and sanding was not the fashion in the forties; those who liked bare boards painted them with the glossy Brunswick Black used for painting kitchen ranges and polished them regularly, as did Sarah. There was a much-resented article on William Roberts by Barrie Sturt-Penrose, published in the Observer colour supplement in 1971. This enraged the Robertses not only because he had bluffed his way in to the house, but also because of his association of bare boards with dire poverty in his description of the interior. Roberts answered him smartly in his witty pamphlet Fame or Defame. 'What kind of art critic is this,' he wrote, 'who sets out to criticise my pictures, but criticises my gas stove and kitchen table instead?'