AN ENGLISH CUBISTElizabeth Cayzer:William Roberts's PortraitsThe 2002 William Roberts Lecture, given at the National Portrait Gallery, London, on 2 February 2002. William Roberts was blessed with a precocious talent. Whilst still a schoolboy special art lessons were arranged for him, and his father, a carpenter, made him a drawing-board and an easel. Furthermore, he encouraged his son to paint his headmaster. In 1909 the boy was apprenticed to Sir Joseph Causton Ltd, a poster-designing and advertising firm, while, in the evenings, he attended St Martin's School of Art. His days were long and intense, beginning at eight in the morning and ending at six in the evening after which he went on to St Martin's, arriving home at 10 p.m. But this was not unusual for a fourteen-year-old: his contemporary Mark Gertler, for example, was pursuing a similar path. Roberts's precocity met with its reward: in 1910 he won a London County Council scholarship to the Slade School of Art based upon the very favourable assessment of such works as this red-chalk drawing of The Artist's Father, Brothers and Sister, dated 1909, which shows six lively heads crowded together on to a sheet of paper partly, no doubt, to save money. |

|

|

and Sister (1909) |

|

Roberts's three years at the Slade were under the rule of Professor Henry Tonks – a stickler for the life class and the fundamentals of good draughtsmanship. At this

the young artist continued to excel, winning prizes and capturing the attention of

Tonks. An Old Man is an example of his style then. The model is an Italian – apparently many Italians were employed by art schools, and during the summer vacations

they turned to selling ice-cream. This particular man had posed, when young, for

Sir John Everett Millais, which he would proudly tell the students saying: 'Me Speak,

Speak', for the painting in question's title was Speak! Speak! This is a fine and detailed portrayal of old age, the folds of the leathery skin,

the sucked-in effect of the toothless mouth, and the wild hair all carefully described.

It is almost romantic in style, but this was but a passing phase for Roberts, who

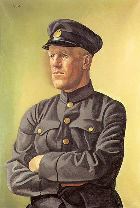

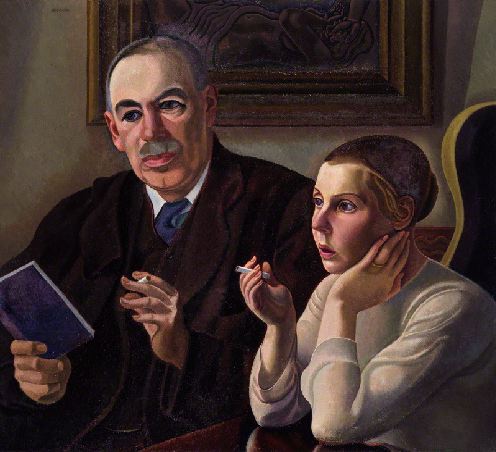

by 1912 was alert to everything modern, while by 1913 he was positively Cubist in style. During the summer holidays of 1911 and 1912 some of the Slade's students were invited to stay for several weeks with various of Tonks's friends in the country; there they were able to draw and paint in relaxing surroundings. Roberts went to the home of Sir Cyril Butler (honorary secretary of the Contemporary Art Society) and, whilst there, he was commissioned to do a series of six London market scenes for him. In addition, the Fitzwilliam Museum have a red-chalk portrait drawing of Butler which Roberts later authenticated, saying that it dated from the visit. And this, it seems, is how a number of his most interesting portrait commissions came about. He never set himself up like, for example, Sir William Orpen or, more reluctantly, Augustus John as a portraitist. He was, and certainly until the later 1940s remained, an occasional painter of people's portraits. I now want to look at four portrait paintings commissioned by people who came to know and admire William Roberts's work early on and who, in the inter-war years, sat to him. They were Rudolf Stulik, the proprietor of the Hotel and Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel in Percy Street; P. G. Konody, the art connoisseur and critic; T. E. Lawrence – Lawrence of Arabia; and the economist and art lover John Maynard Keynes, whose double portrait with his wife, the ballerina Lydia Lopokova, is on view here in the National Portrait Gallery. I will be giving you quite a lot of background information about these sitters, because I feel that it is vital to an understanding of how Roberts responded to their characters, and to what one begins to feel may be missing from that response. Rudolf Stulik was from Vienna, where he had been chef to the emperor Franz Josef. In 1908 he arrived in London and bought Number One Percy Street, hitherto an 'undistinguished' restaurant frequented, according to Augustus John, by 'French business people'. Within a year it had become the place to go, for Stulik – and I quote – had imported from [Vienna] a new note of gaiety and style. Himself the result (as he hinted) of a romantic, if irregular, attachment, in which the charms of a famous ballerina had overcome the scruples of an exalted but anonymous personage, he was in any case well equipped by nature for the part he played The 'Tower' became under his management a favourite resort of poets, painters, actors, sculptors, authors, musicians and magicians [this is John writing still]; not to speak of members of the fashionable and political world. In 1916 the Hotel Review praised 'the excellence of his cuisine and the quality of his wines'; they were second to none in the West End of London.  The Vorticists at the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel: Spring 1915 (1961) How, then, did the young and impecunious William Roberts come to frequent such a smart restaurant? It was thanks to Wyndham Lewis, who can be seen in the centre of Roberts's later painting The Vorticists at the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel, which records events there in the spring of 1915. Lewis had been living in Percy Street since 1914 and having most of his meals next door at the Tour Eiffel. He soon became a favourite of Stulik's, who, according to Roberts, used to tell him: 'I vould [sic] do anyting [sic] for Mr Lewis.' In the earlier part of 1915 Lewis was deeply involved with his new magazine Blast and the promulgation in it of Vorticism. He had gathered a group of adoring, and not so adoring, artists around him. From his next-door flat he swept them round to Stulik's for dinner on a number of occasions, the meals being paid for by a mixture of Stulik's individual style of accounting – which allowed his rich clientele to pay for his impoverished, but talented, clientele – and by these talented young people earning their keep. That is, in the case of Lewis – and later Roberts – making paintings for Stulik's growing, but artistically haphazard, collection. Roberts painted his portrait of Stulik in 1920 when he, too, had come to live in Percy Street. He had by then known the Austrian for five years and had, during the war, used one of the cheap hotel rooms over the restaurant as a base whilst on leave from the front. Number One Percy Street had become something of a haven for Roberts, a place where, after the birth of his son, John, in 1919, he worked on a set of decorative panels for its proprietor while mother and son were left in the tiny attic flat further down the road until it was time for the next meal.  Monsieur Rudolf Stulik (1920) This painting, now unfortunately lost, is like Roberts's painting of Paul Konody – also dating from 1920 – just a head and shoulders. This was a format that the artist liked, for he said that it meant that nothing detracted attention from the face. Even without the personal attributes we are accustomed to see in a conventional portrait painting it is clear that Rudolf Stulik is some sort of an impresario, and probably a foreigner too. The turned-up collar, the bow tie, the moustache, the tilt of the head and the discreetly veiled eyes all suggest this. It is a relaxed, affectionate portrait of the proud proprietor of a famous London restaurant. It complements very well the description given of him by Adrian Daintry. His English was 'guttural and almost incomprehensible' – but this was 'part of his charm. He had tact as well, and knew how to flatter when necessary, and also when to be patient.' And, continued Daintry, his discretion was legendary: 'A certain vagueness had settled round him, perhaps as a result of the strain of his life, with its late hours and conviviality, and it was proverbially difficult to get the truth from him about any of his customers' movements, except by taking the reverse of what he said as probable.' In the picture Roberts has eschewed the mannerist, Cubist style still very apparent in his figurative work of this date, for example The Cinema, now in the Tate Gallery's collection, for a more realist and sensitive interpretation of his sitter. William and Sarah Roberts retained their fondness for Stulik always, and it seems never to have been tinged with any sort of bitterness or doubt, as were some of their other friendships. This fondness is evident in The Vorticists at the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel, painted in 1961, many years after Stulik's death. It shows him holding a plate on which lies a piece of his famous Gâteau St Honoré, which Roberts described as 'a large circular custard tart ornamented round its edge with big balls of pastry'. He and Wyndham Lewis dominate the picture as they did, in different ways, the young artist's life in 1915: Stulik's elegant hospitality is in marked contrast to Lewis's swaggering bulk, whilst a boyish Roberts sits grim-faced, hands folded over his copy of Blast. Historical events are held in a kaleidoscope, the heady days of Vorticism, Roberts's later assertion of his role in it – and independence from it – and Stulik's benevolence all weaving their threads through this finely composed picture. But for the purposes of this lecture the restaurant's style and setting, together with its staff and more racy clientele, are all that needs noting. During 1920 Roberts had another interesting portrait commission, one from Paul Konody, the art critic of the Daily Mail and of The Observer. Konody was born in Budapest, educated in Vienna, and came to live in England as a young man. He was an authority on Old Master paintings and wrote many books on them. He built up an extensive art library which, at his request, his widow bequeathed to the nation. His obituary in the Art News (1933) described him as 'a critic of outstanding ability and kindliness' and one who also had a 'deep sympathy with living artists and an enthusiasm for modern art he was invariably generous to young artists of talent and his support for them took the form not only of verbal encouragement, but outspoken constructive criticism and the practical aid of purchase.' Certainly he was aware of Robert's work by the summer of 1915, for he wrote a review of the Vorticists' exhibition at the Doré Gallery in which the twenty-year-old participated. Although no lover of Vorticism, his critical eye could see that Roberts was an artist to watch In 1917 Konody was appointed the art adviser and honorary secretary of the Canadian War Memorials Fund, whose objective was to provide a memorial in the form of paintings and sculpture to the Canadians' part in the Great War. The Fund was financed by Lord Beaverbrook and Viscount Rothermere, the latter being the proprietor of The Observer. On 1 January 1918 William Roberts wrote the following letter: Dear Konody, This letter tells us two things: first that the young man trusted Konody to act as an honest broker for him, and second that his art was admired by people in a position to further his career – and, of course, I have referred to both Tonks and Sir Cyril Butler earlier in this talk. William Roberts's confidence in Konody, and vice versa, was rewarded, for in September the critic wrote an article on the Canadian War Memorials in Colour magazine, in which Roberts's composition The First German Gas Attack at Ypres is given much attention, although Konody continues to be nervous of the artist's stylistic quirks, concluding: 'the draughtsmanship is superb and vital even when, for the sake of emphasis, strict accuracy is sacrificed.' Paul Konody's portrait commission in 1920 was timely. Roberts was desperately hard up: 'I have been in such a turmoil over money matters as not to know what I have been doing at times,' he wrote to Alfred Yockney, Konody's counterpart on the British War Memorials Committee – also his employers. Indeed, he was selling drawings he had put together for a show in order to make ends meet and to feed his girlfriend Sarah Kramer and their baby son.  The Art Critic, P. G. Konody (1920) The painting has much in common with that of Rudolf Stulik. Again it is a head and shoulders set against a plain background. Konody was aged forty-eight then and in his prime, and Roberts shows an alert, energetic and kindly face. The rapport between artist and sitter seems total; there is none of that withdrawal of communication which would characterise later portraits. A few years after this picture was painted Konody wrote about Roberts's portrait style, interestingly comparing him with the fashionable Gerald Leslie Brockhurst. He saw an affinity with Brockhurst's 'Leonardesque heads – the same clear-cut design, decorative spacing, strong characterisation, clean execution, and colour unmodified by reflection, though Mr. Roberts is mainly interested in the angles and edges and planes of the head, and Mr. Brockhurst in the roundness and tone transitions.' Always, it seems, Konody's criticisms of Roberts's work were considered and just: no wonder that Roberts's admiration for him never dimmed and that he remembered him over fifty years later when Barrie Sturt-Penrose, one of his successors at the Observer newspaper, wrote a highly-coloured article about the artist. Sturt-Penrose, retorted Roberts, is 'not in the same class' as Paul George Konody: how right he was! By November 1922 William Roberts was discussing a very different portrait commission, his sitter a man attempting to run away from fame, for Lawrence of Arabia had had fame thrust upon him partly because of the journalistic exploits of the American Lowell Thomas. As an undergraduate at Jesus College, Oxford, T. E. Lawrence had learned Arabic in order to visit the Crusader castles of the Middle East and make a study of their military architecture. He returned to the area, upon graduating in 1910, as an unsalaried assistant attached to a team of British Museum archaeologists. He was put in charge of recording the pottery being found but also, because of his knowledge of Arabic, of the labour force drawn from the local village. He was much liked by them, and began to involve himself deeply in their culture and their aspirations for total independence from the Ottoman Empire. When war broke out in 1914 Lawrence joined military intelligence in Cairo and the following year began his association with the Emir of Mecca and his four sons which led on to his part in the Arab Revolt of 1916–18. At the Paris Peace Conference he acted as Sherif Feisal's interpreter and adviser, but was bitterly disappointed – although not totally surprised – when the Allies did not honour their promise of independence for the Arabs of the Arabian Peninsula. Lawrence's was a complex character: at once a loner, and independent of many of the material needs of his contemporaries, he yet revelled in company and particularly that of writers, artists and intellectuals. There was an element of the secret about him, especially concerning his experiences during the Arab Revolt. When Roberts met him in 1922 these 'secrets' – along with a terrible guilt for having betrayed the Arabs' belief that he was working to end their vassalage to the Turks – were torturing him, for he had begun to write the story of his two years in the desert. Since boyhood Lawrence had loved books, and so he decided that his story, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, would be produced as a de-luxe, limited-edition book, fully illustrated as well as having included in it portraits of the main protagonists in the Revolt – Arab and British. Along with a number of other artists, William Roberts was brought to Lawrence's attention, and his work for the book soon delighted him.  Sir Henry McMahon (1922) This drawing of Sir Henry McMahon is an example of one of Roberts's portrait drawings for it. McMahon was British High Commissioner in Egypt at the outbreak of war. On first seeing it Lawrence wrote to Roberts saying: 'It's absolutely splendid: the strength of it, and the life: it feels as though any moment there might be a crash in the paper and the thing start out.' Lawrence continued to praise the artist's drawings of the British diplomatic and military personnel for Seven Pillars, but this is certainly the most 'alive' picture of them that I have seen: a leadenness is beginning to creep into his style, as if he is not entirely comfortable with his sitters.  T. E. Lawrence (1922–3) I feel something of this deadness is manifested in the Portrait of Lawrence too. To date, it seems that Roberts has achieved a good result in his portraiture if his sitters 'give' of themselves to him. I am particularly struck by the pictures of Stulik and Konody in this regard, two men who were completely on Roberts's side and massaged his self-esteem so to speak. The situation is rather different with Lawrence, who was in a state of mental turmoil – some of which can be read between the lines of Seven Pillars – and altogether too complicated a character perhaps for a young, shy artist to fathom Indeed, John Roberts in his autobiographical notes described both men as secretive and, as a consequence, felt that it was not surprising that they 'were not close'. In the picture Lawrence is shown standing with folded arms, his blue eyes staring into the distance, his stance and expression very withdrawn. What a far cry it is from Augustus John's interpretation of him as the romantic hero at the Peace Conference in 1919! Various critics have expressed reservations about the picture over the years. When it was first exhibited in 1923 Konody's view was that 'The otherwise admirable portrait of Colonel T. E. Lawrence is marred by an unnecessary, illogical and very disturbing passage of shadow in the plain background along the cheek. Charles Grosvenor, who has made a study of the large number of portraits painted of Lawrence between 1919 and his death in 1935, comes rather nearer to the root of the problem with his harsh opinion that 'This work, like a number of Roberts' other portraits, seems more an expression of the artist's methods than a capturing of the sitter's physical appearance: Lawrence's face is overly full, and the uniformed figure appears more like a train conductor than an aircraftman.' Lawrence, himself, I think was rather puzzled by the painting. On the one hand he wrote to Eric Kennington – who was acting as his artistic adviser for the book – saying 'It flatters me, I think,' while, elsewhere he wrote that he had been made to look 'very bad tempered'. Clearly, although the two men did like each other and, indeed, Lawrence lent the Roberts family his cottage Clouds Hill on more than one occasion, they could not get the full measure of each other. I have already mentioned John Roberts's opinion of their relationship, and the following letter from Lawrence to Kennington indicates how he felt: 'I'm very glad you are helping Roberts. He makes help difficult sometimes, and yet I feel that I would like the oyster if I had any tool strong enough to pry it open.' In the early thirties William Roberts received what I believe to be his last really exciting portrait commission: it was for the double portrait of Maynard and Lydia Keynes. Yes, there was further patronage to come: for example, Keynes introduced him to some Cambridge academics; there were a few portrait drawings done of the military during the Second World War; and his later patron Ernest Cooper sat to him. But the Keynes portrait was the grandest stab at portraiture that he had before withdrawing behind closed doors to paint his family.  John Maynard Keynes and Lydia Lopokova (1932) John Maynard Keynes is best remembered as an economist, 'the cleverest man I have ever met' not only according to Isaiah Berlin but to Bertrand Russell, H. G. Wells and Clive Bell too. However, the author of The Economic Consequences of the Peace – that brilliant attack on the world leaders at the Paris Peace Conference and their ideas for reparation – was passionately involved with the arts. Indeed, he believed that the creative artist was more important than the economist or politician! His greatest friends before his marriage were Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell, and they introduced him to painting and helped him to form his collection. Often he was able to mix business with the pleasure of another purchase, such as when the sale of Degas's collection occurred in 1918. Grant brought his attention to it by suggesting that perhaps his powers of persuasion could get the Treasury to release funds to the National Gallery so that they could acquire some of these paintings. Soon Grant was reading the following telegram: 'Money secured for pictures' and the National Gallery's collection was swelled by the arrival of works by Ingres, Delacroix, Corot, Forain, Rousseau, Manet and Gauguin. And, of course, Keynes also bought for himself while, in 1919, he had the satisfaction of being able to use the money he had been paid for the French translation of The Economic Consequences to purchase pictures from the Degas Studio sale. As a man, there are many testimonies to his character. His conversation, wrote Clive Bell, was 'brilliant. In the highest degree he possessed the ingenuity which turns commonplace into paradoxes and paradoxes into truisms, which discovers – or invents – similarities and differences, and associates disparate ideas – that gift of amusing and surprising with which clever people, and only very clever, can by conversation give a peculiar relish to life.' He was generous with his cleverness, able to translate the incomprehensible into simple language 'with good-humoured ease'. But, continued Bell, 'his supreme virtue was his deeply affectionate nature. He liked a great many people of all sorts and to them he gave pleasure, excitement and good counsel; his dearest friends he loved passionately and faithfully and with a touch of humility.' And Lydia Lopokova – what of her? 'What is this I hear, about Maynard Keynes marrying a chorus girl?' wrote one of his contemporaries. In fact Lydia Lopokova was a ballerina with Diaghilev's Russian Ballet who, in 1918, had won the hearts of her London audiences. One could argue, I suppose, that her performance of the CanCan in Massine's Boutique Fantasque had an element of the 'chorus girl' about it, but there was more to her than that! It is not quite clear when Keynes first met her, but we know that in 1921 he sat night after night in the stalls watching her dance. Lydia Lopokova has been described as delightful, witty, honest, and unpretentious. Intellectually more of 'an untutored intuitively wise little gamin ' than 'the superbly educated intellectual genius' her husband was, she, like him, became distinguished when discussing her area of expertise. Her use of English was particularly winning – though it and her constant chattering drove Vanessa Bell mad – and the letters she wrote to Keynes bear witness to it. In April 1925, shortly before they married, she wrote: ' do cast off your ear-ache. With this cruelty of climate yesterday and to-day, drafts in Cambridge are probably abnormal and that is how the root of the trouble crawled into your ear. Advise cotton wool, 1/100th of a centimetre.' Lydia certainly cultivated this idiosyncratic use of language, for the actress lay within her. She did, however, read widely in English – Keynes had a fine collection of books – and she embraced English culture. Before long artists flocked to paint and draw her: Picasso, Duncan Grant, Glyn Philpot, Laura Knight and Augustus John, who frightened her so much that the sittings were abandoned. She was also sculpted by Frank Dobson, writing happily to Keynes about the work in progress. 'Dobbie's Lydia is charming. She has not the hair yet, nor the last covering of the skin, but she is such as her mother nursed her in womb. (Dictionary also gives uterus but womb is such a beautiful word if I would be poetess I would use it in great many works.)' From this, and from a knowledge of her general enthusiasm for art, I would imagine that she wholeheartedly endorsed the commissioning of Roberts's double portrait. Maynard Keynes's awareness of William Roberts's paintings must date back at least to 1925, when he formed the London Artists' Association in order to help young artists financially and with the exhibiting of their work. He believed that Roberts was one of the contemporary British painters 'whose work will really live', and ranked him alongside Duncan Grant as one of his two most preferred British artists. Roberts's preliminary drawing for the composition shows that his first thoughts for it did not change dramatically. In the final painting Keynes is given a cigarette – both of them smoked a lot – and his book is transferred to his right hand. The artist also hangs one of his paintings on the wall – Keynes owned a total of fifteen by him. All this informs us about Keynes's love of the arts and fine books – his Edmund Spenser collection was enviable – but it tells us little about his personality, less about Lydia Lopokova, and next to nothing about the rapport between husband and wife: nor of their warmth, charm and wit, so obvious to all commentators. Photographs attest to their likenesses here: Keynes by the 1930s had grown bulky and balding, while Lydia was petite with high-cheeked Slav features. Roberts has been careful to make her form rounded and feminine, to contrast the soft material of her sleeves with the heavy cloth from which her husband's coat is made – or is it an overcoat? Both of their faces are heavily worked around the eyes, cheeks and foreheads as if make-up has been applied. Admittedly this is Roberts's manner, though the heightened colour makes it more pronounced. Their hands are bothersome, neither acting as a pair – Keynes's in particular – and they are too mannered to signify the couple's cultural interests. The painting of their hands also troubled Keynes's nephew, who described them as 'rendered with striking artificiality', while Robin Gibson's observations go further: 'A slightly abstracted and reserved work, it does capture something of Keynes' formidable personality ' He continues: 'The two elegantly curling hands holding apparently unlit cigarettes at the lower centre of the picture keep the composition together but scarcely unite the two figures psychologically.' However, it does appear from the documents that Keynes was content with the commission and that he continued to support Roberts financially until his death in 1946. I have deliberately spent time looking at these four portrait commissions, for the sitters were people who showed nothing but goodwill towards William Roberts. I have also described, at length, their characters in order to allow you to see how Roberts reacted to their personalities. |

|

|

|

I now want to turn to some of the family portraits and to look briefly at how the artist saw himself and his wife, Sarah. The photograph above on the left shows how Sarah Kramer looked when they first met – she was aged fifteen – and that on the right Roberts as a gunner in the Royal Field Artillery during the Great War. In 1984 the National Portrait Gallery mounted a large exhibition of these portraits – 'An Artist and his Family' – so I do not want to cover the same ground again. However, I will show you a few of these portraits so that I can go on to relate them to the commissioned portraits and thereby draw some conclusions from all this about Roberts's achievements in this field. |

|

|

|

|

|

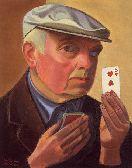

The Self-portrait drawing of c.1920 shows the aspiring artist, stylishly dressed in suit and tie confidently encountering

his face in the mirror. Although the drawing of the jacket echoes Wyndham Lewis's

portrait style of this date, this does not act as an irritant, for William Roberts is in charge of his pencil. The Self-portrait Wearing a Cap of roughly ten years later is rather different. He remains assured, if a touch sardonic,

but he has changed from wearing a suit to dressing himself as a working man in cap

and braces. And so he would continue to show himself in many other self-portraits

over the years. |

|

|

|

Here on the left is a drawing of Roberts at work, one of a group of at least nine

mainly full-lengths. When, in this series, he shows himself as the practising artist

he becomes less self-conscious and his gestures and body language are relaxed for

they are second nature to him. The drawing also shows his skill as designer, the crisp placing

of the figure on the paper with its clear-cut outlines so much easier to accept than

The Card Trick of 1968, with its clumpy, stolid forms and enigmatic message, which some commentators

consider refers to the family trio of himself, Sarah and their son, John. |

|

|

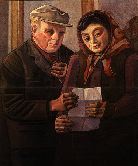

The two double portraits belong to an honourable pedigree of marriage paintings, but

in themselves I find them unconvincing. They make an interesting comparison with

the paintings Stanley Spencer made of himself and his then wife Patricia Preece between

1935 and 1937. That marriage was a disaster but, although Spencer does not set out to

admit it in his paintings, his misplaced infatuation is what shines through. The

Roberts double portraits are the reverse, for theirs was a long and happy marriage.

But, while the Spencer paintings resound with tension – because of the dramatic irony so implicit in them – and tell us about real life, Roberts's compositions are implausible in their demonstrations

of love. The artist and his wife have become part of his generalised gallery of characters.

The 1942 painting is especially awkward: why does Roberts dress himself in heavy winter wear and Sarah in a sleeveless dress? Why the strange hands again?

There is a falseness here as if Roberts cannot, even in a 'marriage portrait', face

the person he really is or talk honestly of his love: the autobiography is incomplete.

When both picture were shown at the National Portrait Gallery in 1984, along with all

the other family portraits, the art critic of The Guardian put his finger on the problem:It seems extraordinary that so much painting over so many years should leave us so ignorant of the true nature of the people hiding behind the famous William Roberts manner, hovering elusively between the stylised and realistic 'Bobby was not a pub man; he got his copy from looking through the windows,' explained Sarah. She was referring here to his figure compositions, but her words apply equally to all the portraits. T. E. Lawrence's 'oyster' never worked its way out of its shell; rather it became deeply encrusted within it. The portraits of Stulik and Konody, together with all the other work done by Roberts in the 1920s, are interesting pieces, but when the props of kindliness were removed he faltered. Diffidence, a propensity to take offence, artistic feuds – such as the one with Sir John Rothenstein at the Tate – when they muddle the eye do not make for the best portraiture. The finest portraits are those in which the painter gives himself over completely to what lies before his eyes and does not allow his own personality to interfere with the evidence. In my opinion, the prerequisite for a successful portrait is a fascination with, even a love, of people. In addition, the artist's active imagination and analytical mind are essentials, The greatest portraits have a universality about them, and in twentieth-century Britain I believe that the portraits painted by Graham Sutherland and Maggie Hambling fall into this category. Their vision is fresh, filled with wonder and inquiry linking them to a long line of artists – Titian, Rembrandt and Van Gogh among them – who repeatedly grappled with the complexities of the human psyche. Common to all of them is a perennial vitality and a permanent relevance. But let me not end on a negative note as far as William Roberts is concerned: his work will live on. His portraits of the 1920s – including those of Sarah – and the portrait of John Maynard Keynes and Lydia Lopokova are distinguished, and, in the words of his obituarist in The Times, his reputation as a portraitist is 'deservedly high'. Home page | Chronology | Bibliography | Collections | Exhibitions News | Gallery | Auction results | The artist’s house | Contact List of works illustrated on the site Catalogue raisonné: chronological | alphabetical |