AN ENGLISH CUBIST

PAULINE PAUCKER:

Sarah: An Anecdotal Memoir

of Sarah Roberts, Wife, Model, Muse and

Defender of William Roberts RA

Illustrations and poems © The Estate of John David Roberts.

Other text © Pauline Paucker, first published by the William Roberts Society, Tenby, 2012

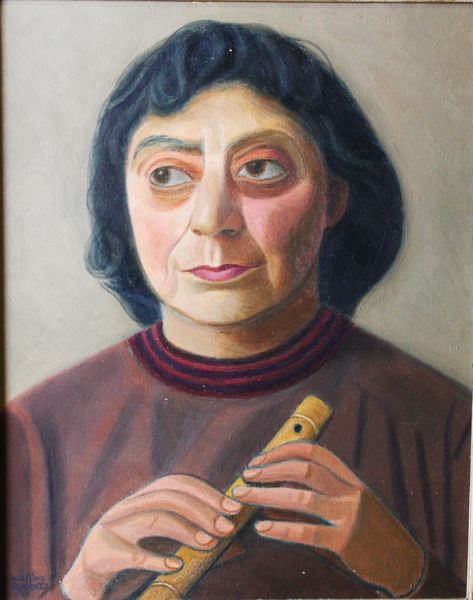

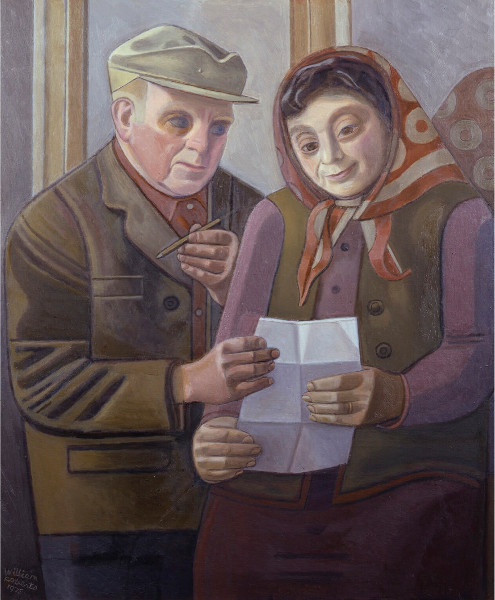

The Reed-pipe, a 1971 portrait of Sarah with the

pipe she made and played in a pipers group

First encounter

Shortly after we moved into our house, in the 1960s, a motorway-box scheme threatened to destroy it together with a large slice of the area north of Regent’s Park and other areas of London. I was appointed to the hastily organised local protest committee as an extra token woman among the town planners and architects of the neighbourhood.

At one meeting fund-raising was discussed. ‘Coffee mornings? The Archway people have those.’ ‘A jumble sale? Can be quite successful.’

‘I was speaking to Mrs Roberts the other day – you know, the wife of the artist, William Roberts; they’re in St Mark’s Crescent. They’re very anti the motorway scheme, and she said she’d be willing to organise a jumble sale to raise some money … ’

‘But they’re rather reclusive, aren’t they?’

‘No, no, that’s him. She’s very sociable.’

‘Is there someone who’ll contact her? Pauline? Yes? They’re in the phone book.’

When I rang her, Sarah asked me to come to tea the next day.

She was outside the house, on the steps, talking to a neighbour, and gestured to me to wait. Pink-cheeked, a softly wrinkled face, abundant silver-grey wavy hair, wearing a pinny, she looked like an old-fashioned countrywoman.

She ushered me down the sharp-edged flight of concrete steps at the side of the house – how often was I later to scuff my shoes walking down them! – and in by the side door to the basement sitting room looking over the garden and canal.

‘I have to finish my guitar practice, do you mind? Do you play? No? You know, music is a great solace as you grow older.’ Seating herself in a corner by an ornate music-stand, curiously out of keeping with the simply furnished room, she began to play, hesitantly, with many pauses.

‘My son is teaching me by his special method,’ she said.

There was a Roberts painting over the fireplace – gypsies lighting a fire in a wintry wood – and in a corner a watercolour of what could only be the son, John, guitar case on his back, asking the way of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. I was used to seeing Roberts’s work each year at the Royal Academy’s summer shows, it was very familiar, but I decided it was not the right moment to make a comment: Sarah was still plink-plinking at her guitar.

Instead, I went over to the bookcases on either side of the fireplace.

A nice selection, mostly linen-bound, with faded backs. George Moore’s Ave, Salve, Vale, in a better edition than mine; Andrew Lang; Edmund Gosse – essays, and his Father and Son. There were the Russians: Turgenev, Tolstoy, and here was the same small-format green-linen set of Constance Garnett’s translation of Chekhov’s short stories which we had. Hazlitt, Charles Lamb, Gissing – a very nice collection, I thought, someone to talk to here, people of pleasantly old-fashioned taste. And ah! Seven Pillars of Wisdom, popular edition – surely Roberts had done several drawings for this? Next to it a one-volume edition of Doughty’s Arabia Deserta; well, I had the two-volume set … Here Sarah called me away for tea.

Later, John and Sarah told me that they had felt I was an acceptable friend because I had gone straight to the bookcase to handle the books; but then I too was a collector.

Tea was made, Sarah taking me into the charmingly furnished kitchen: pots and pans on shelves, a wooden kitchen table, chunky cupboards, and a baby gas stove. It was rather strong tea which she brewed – the Robertses favoured the Typhoo Tips brand. She had prepared buttered tea-matzo biscuits and home-made rocklike rock cakes. We carried cups, saucers, plates back to the sitting room to sit at a small, round pedestal table in the bay window.

As we talked she told me of her son, who she was sure would like to meet me – ‘an attractive man of fifty’ she said.

‘And do you have a car?’ she asked.

‘No, I walk.’

’Well, you shall be my walking companion. So many of my friends have cars, they don’t want to walk. So that’s fixed. I’ll call you.’

There had been no discussion of motorways or of jumble sales, but on the day Sarah presided over a stall. The motorway-box scheme was eventually abandoned owing to a change of thinking, lack of money and, we hoped, opposition from the public.

On foot with Sarah: the first outing

‘My friend Norah Meninsky and I are going out walking on Hampstead Heath. Would you like to join us? I’ll come round the corner to collect you and we’ll take the no. 24 bus up. Norah will meet us there.’

Norah, large and handsome, was, as I had guessed, the widow of William Roberts’s artist friend Bernard Meninsky, his second wife. His first, Sarah told me later on the way home, had run off with a very good-looking chemist living opposite them and had left him with two small boys to look after. Norah, she said, had coped splendidly.

‘She was one of Cochran’s Young Ladies, in the chorus, though I wonder how, with those legs, don’t you?’ There seemed no answer to this.

As we walked from the bus across to the Heath, Sarah darted into one or two shops on the Green. Norah called across, ‘Sarah, come out of there, we are here to walk on the Heath. You have a butterfly mind.’

Norah, I found later, believed herself to be intellectually superior to Sarah, who often played the fool to disguise her innate shrewdness.

We were soon moving swiftly towards Kenwood, Sarah then in her late sixties and still a brisk walker, Norah likewise. They were exchanging anecdotes of their pasts, scandalous stories of friends of long ago.

Sarah, feeling I was left out, turned to me and said, ‘You must excuse us. One of the few pleasures of old age – and let me tell you there are very few – is finding out about people you knew, rounding off their lives. You read an obituary or a biography and then you see why she played that dirty trick on you or why he disappeared so suddenly.’

Here she turned back to Norah, who was saying, ‘I’m not suggesting that she was always on the game, but after he left her there was certainly an episode.’

‘Well, it would have been before she went to live with what’s-his-name and probably no more than an episode. Even so … ’

And on they went.

‘I know every path on the Heath,’ said Sarah, pointing out to someone the way.

He who must not be spoken to

When one met Sarah in the street with her husband – ‘Bobby’, as she and John called him – she would stop to talk and he would either walk on slowly or stand a little aside, smiling vaguely, which obviously would shorten the conversation.

Some people were offended by this refusal to speak to them, but surely this was his chosen way, which I respected. Certainly he was never offensive. He was obviously painfully shy, and so was his son, John. They both relied on Sarah to a certain extent for much of their contact with the world.

One day soon after I had met her, coming back from a joint outing to a gallery, I noticed that she had left her umbrella on the bus. I walked back the one stop to St Mark’s Crescent and knocked on the front door of no. 14 thinking Sarah would be there to open it, having just got home.

But the mottled glass of the door panels showed the red and purple blotches of Roberts’s high-coloured face. ‘Who is it? What do you want?’ he called petulantly, without opening the door.

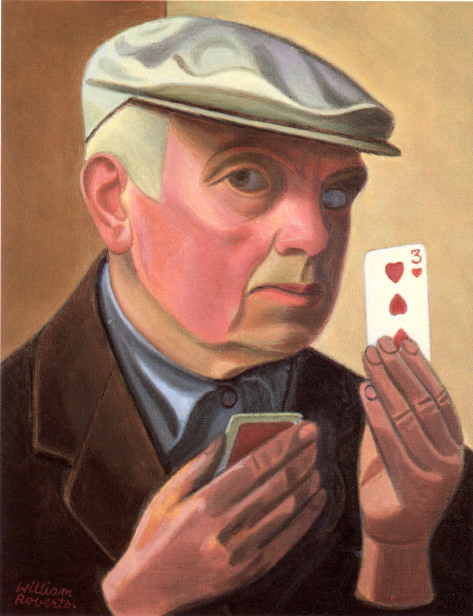

The Card Trick, 1968

I knew that he was ‘he who must not be spoken to’, and that the front door was not to be knocked at – especially after an intrusive journalist had recently gained entry and written a denigrating article for the Observer colour supplement, which rankled.

I shouted through the letterbox that Sarah had left her umbrella on the bus and that I would push it through.

There was a pause, and then he bent down to the letterbox saying, in a strangled voice, ‘Thank you very much.’

This was the first time he spoke to me. He was to speak to me once more.

Introduction to John

I was eventually introduced to John, over tea, and realised that I knew him by sight: a burly, grey-haired man who would walk with a curious swinging motion round the corner of Regent’s Park Road on his way to the Camden Town buses, or be seen in the park, talking to himself – composing a quatrain no doubt, in his role as a poet.

We talked about book-buying: he had been a runner, and was still dealing in a small way. He disapproved of our never having sold a book and preferring to give away any duplicates. ‘Bad for trade,’ he said.

We invited him to come with Sarah and look at our collection of books. After tea he rose and, first wiping his hands on the seat of his trousers, selected a book to inspect, pushing in the books at either side a little before taking the spine of the one chosen by the middle, carefully pulling it off the shelf. He then opened the book at forty-five degrees and squinted at it.

Plainly John was a man to be trusted with a library. We were very impressed.

Parents, brother, sisters

Sometimes Sarah spoke of her parents’ life in Russia. That her father, Max Kramer, had been a pupil of the great Russian artist Ilya Repin was regarded by John with some scepticism: he thought it highly unlikely. I once heard him challenge Sarah on this, and she became very defensive – and annoyed.

Certainly Jews were mostly barred from institutes of higher education in tsarist Russia; but there were exceptions, and her father may well have been one.

Only one small painting by him had been displayed in their Leeds home – a landscape – but it eventually disappeared and Sarah said she could hardly remember it.

Her mother, Sarah told me, had been the daughter of a farm bailiff – Russian Jews were sometimes employed in this way. Cecilia had grown up in comfort on the prosperous estate, but after her mother’s death she found life with her stepmother impossible and joined a small travelling opera company which was visiting the town.

She had a good voice, had had singing and piano lessons, and learned quickly.

The Russian bass Chaliapin had begun his career in just such a company, but no career like his awaited her.

She gave up the stage on marriage, but retained a repertoire of operatic arias and Russian folk songs.

She also retained her faith, keeping a kosher household in Leeds, though Sarah remembered her reading her prayer book at home on the Sabbath rather than going to the synagogue, where the family could not afford seats. Her father, it would seem, had become less observant of the faith over the years.

Sarah often told friends the anecdote of how as a young girl she resentfully had to cross the town carrying a trussed live chicken to be ritually killed by the shochet, something she thought ridiculous. ‘It put me off religion for life,’ she would say. But, obviously, for her mother it was cheaper to buy a live chicken in the market than one from the kosher butcher’s shop. (I wonder how her mother fared when visiting her daughter in London, in a household where breakfast began with forbidden bacon.)

Both Sarah and William Roberts disliked all forms of organised religion, but had their own ideas of what religion should be.

Sarah’s stories of how the Kramer family arrived here echo those of so many immigrants before 1914. The world was then open: no passports, no visas. Sarah said that they had bought what they believed was a passage to New York, but, cheated like so many others, they were dumped on a dockside somewhere in England.

There are some questions about Sarah’s place of birth. Born in 1900, she said, she does not appear in the 1901 census. Was she born in Russia like her brother Jacob? Or on the boat? Or in England? Census forms were often not filled in accurately by fearful new arrivals who had come from repressive police states.

William and Sarah married in 1922, three years after John’s birth, around the time of Sarah’s first trip abroad. Perhaps they married in order to give Sarah a British passport, if she had not been born in England.

On arrival, the Kramer parents made contact with a Landsmann, a fellow townsman, who told her father that there was a job going for an artist, in Leeds. There was a Jewish firm of photographers which found customers in the immigrant community. Specialising in portraits taken from old photographs, they wanted an assistant.

‘They went round knocking on doors,’ Sarah said, ‘and asked for photographs to enlarge, or they would offer to do a portrait of someone’s parents. It was quite lucrative, but they paid their staff badly.’ Certainly it proved to be ill-paid, weary hackwork for her father.

Her parents chose not to live in the Jewish quarter of Leeds, but kept apart from the main community, feeling themselves superior to the immigrant shtetl Jews, the rural and oppressed Jewish poor of Russia and Poland.

Literature, music and art were an integral part of Kramer family life.

Her brother Jacob’s heightened stories of his adventurous childhood were not repeated by Sarah when she reminisced, nor did she speak much of his precocious talents as an artist. She talked rather of herself and her sisters, Millie and Leah – how they would walk against the wind hand in hand on the moors outside the town pretending to be the Brontë sisters – and of Friday-evening entertainments put on by the children for their parents. Millie would dance, Sarah recite, Leah performed in some way, and always Jacob ended by dancing an energetic kazatsky.

Cecilia, Millie and (on the right) Sarah Kramer

Sometimes their mother would sing for them, their father happily smoking, he the evening’s non-performing audience.

Up to London

Sarah was intelligent and won a scholarship to the local grammar school, but was hampered by the family’s poverty. ‘There was hardly any money for books and uniform, and I never owned a hockey stick or a tennis racket. There were other girls in the same position, and we stuck together. It wasn’t easy.’

Jacob, as a Leeds School of Art student, had had contact with a Bradford gallery and could earn a guinea or half a guinea with a portrait drawing. Drawings of Sarah – by now a beautiful young girl, often dressed up as an Augustus John-style gypsy – sold well. Sarah herself bought a few when they came up at auction when she was quite old.

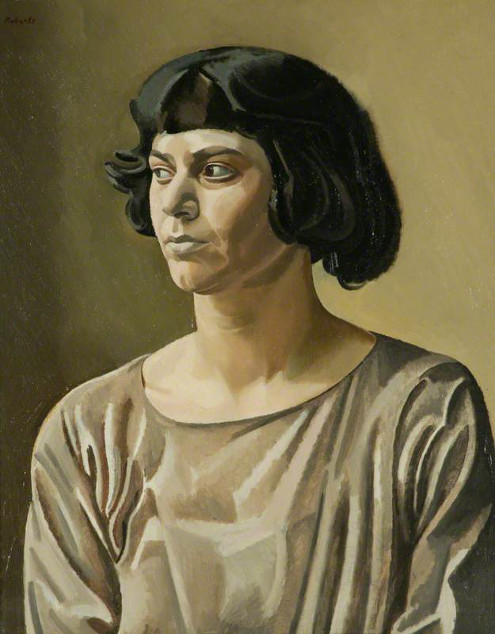

An early drawing of Sarah by her brother, Jacob Kramer

The money Jacob received helped the household to keep afloat, but posing for hours after school meant that Sarah fell behind with her schoolwork and her dream of becoming a teacher faded.

Jacob’s idea was that with her striking good looks she should go on the stage – as a dancer maybe, or an actress. Studying at the Slade, he knew people in London who might promote her.

Now she dreamed of going up to London.

When she was fifteen, and on holiday from school, Jacob arranged for her to visit him; she stayed with David Bomberg and his wife.

‘Jacob’, she said, ‘showed me off to his friends like a jewel. It was very embarrassing.’ One afternoon he introduced her to William Roberts, in an ABC tea room – a meeting that was to lead to a very different life: to ‘love among the artists’ as she called it, a favourite phrase with which she often ended an anecdote.

‘Well, that’s love among the artists … ’

‘Love among the artists’

By this Sarah meant living in poverty, from hand to mouth. She had had some experience of this when living in Leeds, but it was a way of life of which some of her friends who had taken their pretty faces into artistic circles soon tired, and they married wealthy businessmen instead. ‘And yet,’ Sarah said once, describing just such a transition, ‘they still envy me, married to an artist. They’d like both.’

Living in a room or rooms, sharing a lavatory, with a sink maybe on a landing, with a money-in-the-slot-meter gas fire and gas ring for heating and cooking requires skills of a kind Sarah had aplenty.

A Roberts painting of a woman washing a small boy, a basin of water on the floor, may well be of Sarah washing John in their cramped quarters.

‘We knew how to have fun, though,’ Sarah reminisced. ‘Some of us would make up parties to the public baths. Living in rooms, there was no way of washing clothes or having a proper bath. We’d take our bundles and some lunch and make a day of it with the other women – real London types. We’d have a laugh together.

‘But, you know, to be poor – really poor – means that a friendship can be broken through the loan of half a crown not paid back. People today can’t imagine just how poor we were in those days.’

Cecilia Kramer

Sarah said that her mother, to her surprise, accepted her relationship with Bobby and developed a genuine affection for him; they got on very well. His painting of Sarah and Cecilia, Jewish Melody, is – or was – a great tribute to mother and daughter, but now exists only as a black-and-white photograph. For some reason it was destroyed, and only the cut-out head of Cecilia Kramer remains. I once asked Sarah and John what had happened to the painting when we were looking at a catalogue in which it was reproduced. They looked uncomfortable and changed the subject.

Jewish Melody: Sarah and her mother, Cecilia, painted 1920–21

Cecilia occasionally came up to London to stay with Sarah and Roberts. The elder daughter of their friend Esther Lahr (Roberts’s striking portrait of her is in the Tate) recounts a story of the two Jewish mothers, Sarah’s and Esther’s, refusing to meet one another though sitting on adjoining benches in Regent’s Park. Both were mothers of daughters who had broken loose from the restraints of Orthodox Judaism and bourgeois respectability and should have had something in common, their daughters thought; but no …

Afternoon tea

During William Roberts’s lifetime Sarah’s only possibility of entertaining friends was at teatime, but at six o’clock Roberts himself came down and Sarah then had to ask her guests to leave. ‘Shoo! Shoo!’ she would say, and guests left by the side door or, if it had been a fine day, by the garden gate. Sometimes Roberts came down early and if guests were still in the sitting room he would go into the garden and sit on the wall supporting the small lawn; once I noticed him looking at us impishly, waiting for us to go (in what John called his leprechaun mood). In summer, if tea had been served in the garden, he would bumble about in the sitting room, very visible in the bay window, and guests would be shooed out.

Tea-matzo biscuits, buttered, Sarah thought were very nice, and digestive biscuits. The Robertses were connoisseurs of digestive biscuits, and believed that there were certain days when they were delivered to the supermarkets when one could be sure of their being fresh. Sarah, as a Yorkshirewoman, should have been a good baker – certainly she was a good cook. But her rock cakes were all too rocklike. Puzzled, she would say, ‘But everything I put in is good.’

Tea was served at the small pedestal table in the bay window, or, when in the garden, on a folding table; a too-small teapot meant going in and out of the kitchen to refill. Teapots were a problem, and the kitchen shelves were ornamented with failures, often made by potter friends but too liable to drip and so banished.

Guests were a mixture of old friends and new; numbers varied from two or three to six or seven, John sometimes present, sometimes not.

‘Not enough trousers,’ said one disgruntled woman guest, around Sarah’s age, herself wearing trousers as I pointed out to her. ‘I mean men,’ she said crossly. Maybe John didn’t count.

But Sarah was also likely to say, at a party, ‘Where are the men?’

The tea-table test

After Roberts’s death, would-be purchasers of the smaller works would be invited to tea by Sarah and John and shown a small selection of the work they were willing to sell. Negotiations for larger pieces took place in the first-floor front room, where the paintings were stacked.

American buyers were regarded with suspicion, and I, as a frequent traveller to the United States, would be asked to be present when an American was a guest, presumably being regarded as someone who could speak to the natives

Two American Kramer cousins were made welcome and bought paintings, but an American friend of mine had to undergo two tea-time tests and eat her rock cakes before being declared to be ‘a very nice woman – for an American’. She was then allowed to buy two watercolours, though one was withheld for a while in case they could buy back the missing piece in the series of sketch, squared-up drawing and watercolour to match the large painting they still owned. It was a scene of visitors to the zoo, the monkeys gazing accusingly at the people watching them, and my friend, a sociologist, said she wanted that particular watercolour because of ‘the body language’ – which fashionable expression rather disturbed Sarah and John: ‘What’s body language? What does she mean?’ But she was finally allowed to buy it, they telling me that they had been unable to buy back the missing piece they had sought.

One American curator, who wished to borrow a self-portrait of Jacob Kramer, owned by John, for an exhibition in New York, failed the tea-table test.

It was winter, and Sarah had served buttered crumpets. ‘What’s this?’ asked the American woman, looking at her plate with distrust.

‘It’s a crumpet,’ said Sarah.

‘A relation of a muffin,’ I said.

‘It’s a traditional English tea speciality,’ added Sarah. ‘Why don’t you try it?’

‘Uh-uh,’ said the visitor, pushing her plate away.

John looked at Sarah and Sarah looked at John; they were shaking their heads.

‘Now, where’s the portrait?’ asked the curator, all professional.

John went upstairs and came down with the very dramatic self-portrait of his uncle. (‘John resembles his uncle more than he cares to think,’ Sarah once said to me, rather crossly, but I never knew in what way.) He displayed it against his chair, and the vividly drawn head seemed more alive than we were as we gazed at it.

‘Oh! That I have to have!’ said the excited curator.

‘Well, I’m not lending it,’ John said. ‘I’ve changed my mind.’ And he packed it up, much to the astonishment of the American visitor.

Smoking

Sarah smoked just three cigarettes a day – one after mid-morning coffee, one after lunch, and one after supper – seemingly with great enjoyment. She smoked in the way many women of her generation did: not inhaling but puff-puffing, flourishing the cigarette with extravagant gestures as though performing a daring act.

There is a beautiful watercolour portrait of her smoking: she’s standing, her arms crossed, cigarette in hand, her head arrogantly turned to one side.

Sarah, 1923

Aged twelve or thirteen she had taken to stealing cigarettes from her father’s desk to smoke with one or two friends from school. They would go to Jacob’s rented cottage outside Leeds to enjoy them, feeling, she said, wonderfully wicked.

Her father was a heavy smoker – it was to lead to his early death, she thought, combined with the effects of the fixative used in the photographers’ studio where he worked.

One day he caught her rifling the cigarette box. ‘He put me across his knee, pulled down my knickers, and spanked me. I think it gave him quite a kick,’ she told me, laughing. ‘But I forgive him. I bear him no grudge. And it didn’t stop me smoking.’

14 St Mark’s Crescent

Sarah sometimes wistfully spoke of their pre-war London flat: so pleasant, so nicely furnished – they’d been able to buy things from Heal’s, she said. In 1939 they had evacuated themselves to Oxford; it had been a difficult time. She would occasionally speak of the Second World War as though it had been a personal insult: ‘Bobby was beginning to do quite well,’ she would say, ‘and then came that dratted war.’

‘We were so lucky with this house. When we moved in it was only just after the war, when we came back from Oxford. It was a lodging house then, full of people. We moved into the front room with a bed, an easel, a table and two chairs, and a hotplate.

‘Well, I was used to that: that’s love among the artists – we lived in one room in Albany Street when John was small; Regent’s Park was his playground.’

The people downstairs, with whom they shared the bathroom and lavatory, were a motley, rowdy crew, a family waiting for the husband to finish a prison sentence for bigamy. The grandmother, nicknamed ‘Old Mother Dry Rot’ by Roberts, had had to be bound over to keep the peace after attacking Sarah with a soup ladle. (She appears as one of the mothers in his 1955 painting The Rape of the Sabines.)

The husband came out of prison, chose this family, and off they went back to Wales, the Robertses taking over their quarters. Then the main tenant left, with assorted subtenants, and the Robertses remained as sole tenants protected by the then Rent Act.

‘The owner wanted to get rid of the property, but he couldn’t get rid of us so he offered it for £1,200 and my good friend Victoria put up the money – wasn’t that wonderful? She took some paintings in return, but it was without strings.’

Roberts used his inherited carpentry skills to make cupboards, shelves, dividing doors, a landing stage on the canal at the bottom of the garden for their new-bought boat, and Sarah ripped up the rotting carpets, swearing she would never have any. ‘It took months to get all the nails out, and then I stained the boards with Brunswick Black – you know, the stuff used for painting grates: it polishes up nicely.’ It was particularly irksome that the journalist who later bluffed his way into the house wrote of the bare boards as though they spelled naked poverty.

She referred to this quite often.

‘Why did you ever let him in?’ I asked once.

‘I asked Bobby that – he let him in at the front door. He said he thought it was the milkman, and this man just pushed past him into the house and he couldn’t turn him out. I gave him a coffee in the kitchen, like a mug – in a mug – and then he wrote that stuff for a colour supplement. Did you see it? It was disgusting. Have you seen Bobby’s pamphlet answering him back? I’ll let you have a copy: Fame or Defame. It’s very good.’

They bought furniture from the mixed antique-cum-junk shops then in Regent’s Park Road and from Reggie’s stall in Inverness Street nearby – nice pieces, Arts and Crafts chairs, among them a couple of Gimson chairs and some by Liberty, several nineteenth-century round pedestal tables (they liked these), and Victorian armchairs and sofas. A kitchen cabinet had very solid replacement cupboard doors made by Roberts, and he devised impressive bolt-and-toggle fastenings for the larger doors he made in the house.

A friendly upholsterer in Clerkenwell re-covered chairs and sofas with handwoven fabric bought from weaver friends, in the earthy colours approved by the Robertses: brown, grey, yellow ochre, plain or striped, no patterns. Bookshelves were made to fit in the alcoves; kitchen shelving included racks for trays and teacloths.

They achieved a Spartan elegance suited to the display of Roberts’s paintings in the kitchen, the sitting room, the bedroom.

Sarah had once been invited by a wealthy patron to see the new interior-designed house they had bought in Hampstead. ‘Ghastly,’ she said. ‘We went all over and, do you know, not a book to be seen – must be some kind of savages. But they buy paintings!’

The washing line and dyeing today

Sarah was the last person in the Crescent to hang out washing – something her neighbours did not like. The Robertses had a D. H. Lawrence attitude to household tasks: washing and hanging-out on the line was a ritual of bowls, wooden pegs and wicker peg basket, starting with the careful hooking of the washing line on to a sycamore tree which encroached on the neighbouring garden of Lord St Davids. While sheets and towels were taken to a local laundry, smaller items were washed in the double kitchen sink and hung out to dry. One or two ragged garments were usually included ‘to annoy the lord’, as Sarah would say.

Clothes were dyed to dull down too-loud stripes or to fit in with the muted colours that she and Roberts preferred. Some people referred to their wearing Oxfam clothes, but that was not entirely so. She bought in charity shops because they could not afford to pay much; she was clever with her needle and would alter and dye dresses for herself, also dyeing shirts for Roberts and for John, russet-brown or a dull green the favoured colours. Friends occasionally gave her clothes, and she had also made her own. She had made hats and ties too in the past, and these can be picked out in Roberts’s portraits. Later a friendly East End dressmaker, wife of the upholsterer, made up coats and jackets from cloth also bought from weaver friends.

Dyeing clothes was something she did with skill and enjoyment: bowls of water on the floor for soaking , a vigorous wringing-out of the fabric, plunging it into the dye mixture in the sink, stirring it as though in a witches’ cauldron, and then out on to the line to drip colour on the grass.

‘I’m dyeing today,’ she would say to friends on the phone – rather disturbing to hear when she became very old. ‘Is there anything you would like dyed? It’s green, ’ or ‘ …It’s brown.’ Sometimes it was blue, never red; the dark yellow and pale blue of the upholstered sofas were the weaver’s colours, as were the soft-coloured stripes used to cover the chairs.

Victoria Kingsley: a friendship

They were the same age and had met when they were in their early twenties, studying the guitar. Victoria became quite proficient; Sarah never did. Both had been pupils of a Madame Kramer – a coincidence which Sarah, née Kramer, found amusing.

Like Norah Meninsky, Victoria took a pose of being intellectually superior to Sarah, based on her having read English at Oxford – Lady Margaret Hall, as she would stress.

This needled Sarah.

Victoria, I was told, lived off the income from inherited capital (made in trade, Sarah liked to point out), the capital to be kept intact, if possible, and handed on to a future generation. So it was a very generous gesture of friendship for her to have given the Robertses the money to buy 14 St Mark’s Crescent as an outright gift. In gratitude she was given some paintings, which were later to prove more valuable than at the time, in the late forties.

This gave the Roberts a security which so many of his artist contemporaries like Mark Gertler or David Bomberg never enjoyed, condemned to move from place to place. All three Robertses were to remain in the house till their deaths.

Sarah said that Victoria had made a career as a singer-guitarist, travelling with a varied repertoire of English, French, Spanish songs and folk songs, but in a dilettante sort of way, never having had to earn her living. She had been a pretty young woman with a pleasing voice and an attractive stage presence. When I first met her she was over eighty, a commanding figure, then busily writing her autobiography.

Her chosen title was ‘Flowers in My Bath’, because, she explained to me, on foreign tours the floral tributes from her admirers would overflow from her hotel bedroom into the bathroom, filling the bath.

Sarah one day handed me a wodge of typewritten sheets saying, ‘This is what Victoria has written so far. You read it and tell me what you think. I don’t think it’s very good. It’s very self-regarding and rambling, and she’s got no sense of humour – never had.’

I don’t think it found a publisher.

John made no comment on her writing, but he found her difficult and she him – their views on the guitar were opposed.

The right gesture

One sunny day, after we had crossed the park to Baker Street, a seemingly empty open-topped tourist bus pulled up at a nearby stop. Three unauthorised passengers on the top deck – three young boys who’d sneaked a ride – were being shouted at by the driver to get off. They jumped down on to the metal roof of the bus shelter, the crash as they landed sounding like an explosion – and this was at a time of IRA activity in London.

The few women waiting in the shelter screamed in fright; the laughing boys bounded on to the pavement and ran, ducking and weaving among the people in the street.

Sarah, coming up, put out her left arm and grabbed one of them in a skilled move, swinging her other arm round to clout him on the head. He ran off yelling with indignation.

I was struck by Sarah’s rapid response to the fleeing boy – it looked like a drawing by Phil May for Punch: the snatch, the cuff, the boy ducking, his arm up to shield himself.

‘I’m not saying you did wrong, no,’ said a passing man, ‘but you could be had up for assault. Do you know that?’

Sarah ignored him and marched on to board the newly arrived 274 bus. The women who’d been so startled were already sitting there and telling the other passengers what had happened, pointing to Sarah with approval and miming her actions: ‘She grabbed one of them like this and biff! That lady there!’

Sarah ignored them and pointedly talked to me.

The rightness and vigour of her gestures can be seen in so many of Roberts’s paintings for which she had posed: pinning up a dress, beating a rug, scrubbing steps, washing a child.

‘I can’t come out today, I’m posing,’ she would say. It was obvious that it was not only for the usual portrait that she was the model: Roberts needed no other.

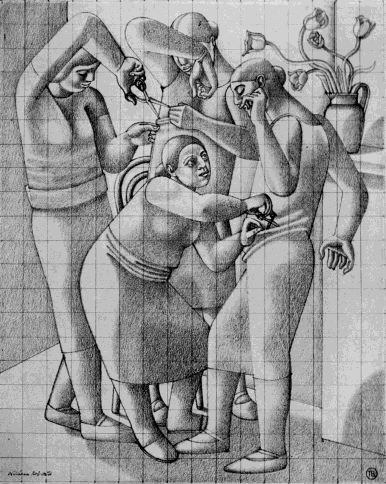

The Try-on – study for Dressmakers, 1931

The parting shot

Sarah was good at parting remarks which left her hearers amused.

One day, passing a shop in NW1 called ‘One Night Stand’, she went in, curious to know what it could be.

Two handsome, rather gloomy women sat there alone, dispirited, a rail of evening dresses on one side of the shop, matching accessories on the other.

‘What are you? Oh, I see, dress hire? For an evening out?’ asked Sarah.

They stared at the tiny, elderly, grey-haired woman.

‘“One Night Stand”? Isn’t that rather vulgar?’ said Sarah, casting an eye on the line of fancy frocks. ‘Well, I’ll keep it in mind – you never know your luck, do you?’ And she bounced out, leaving them laughing.

Photographs

One day John rang me up when I was working at home to tell me that Sarah had not been well: some kind of flu, he thought, unusual for her to stay in bed for a few days.

Could he ask a favour?

He had an appointment at two o’clock, his father didn’t want to miss his afternoon walk, but they didn’t like to leave Sarah alone. Could I come and keep her company?

I could find an hour after three o’clock, but who would then let me in? I asked.

‘My father,’ said John.

‘Your father?’

‘It’s all right, he knows perfectly well who you are. Knock on the front door, not the side. And thanks – I’ll be back by four.’

How to deal with he who must not be spoken to? I decided that I would bow slightly and walk silently on when he opened the door.

I knocked, and his high-coloured face became visible through the mottled glass of the front door, which he opened slowly. He stood back, I bowed and made to move on down the hall, but he put his arm out, like a traffic policeman, to stop me. It was not easy for him to speak – his face became purple with the effort.

In a strangled voice he said, with emphasis, ‘This is very good of you.’

‘Not at all,’ I replied, and tried to walk on.

Again he stopped me: ‘Sarah’s bedroom is the second door, on the right.’

‘Yes, I know – I have been here before.’

Perhaps he thought I might mistakenly try to enter the sacred studio, first door on the right. Even the front door was banned to visitors in Roberts’s lifetime.

His voice was high-pitched, rather Bloomsburyish, an upper-class accent of the twenties. It would seem that he and Sarah had worked on their voices: there was no trace of Leeds in Sarah’s speech, whereas her sister Millie retained her Yorkshire tones.

Sarah, 1922

Sarah was sitting up in bed – the bed they had bought from Heal’s pre-war with its handmade mattress; the bed they still shared.

We heard the front door shut and were now alone.

She had a box of photographs in front of her: ‘I thought they might entertain you,’ she said. ‘But first will you do me a favour? Look under the bed, will you, there are some baked potatoes there. I want you to get rid of them. You see, all they could produce for themselves to eat was baked potatoes, and they served me with them and I couldn’t eat them – couldn’t eat anything. But I don’t want to offend them so I’ve been putting them under the bed.’

She thanked me for the fruit and biscuits I had brought, thought she could now eat something, and I could use the bag I had brought the stuff in to carry away the potatoes, couldn’t I?

‘Now for the photos,’ she said.

She took out first a photograph of herself at fifteen, all goo-goo eyes, abundant dark hair, a peach. ‘How could I have stayed in Leeds,’ she asked, ‘looking like that?’ This was the Sarah her brother Jacob had shown off ‘like a jewel’ as she described it, and the Sarah to whom Roberts had first been introduced in an ABC tea room in London.

She had had offers of marriage while still in Leeds, she told me. ‘I might have married a Jewish businessman and belonged to the Leeds Ladies Luncheon Club. Imagine!’

Her next photograph was one of her holding a small shyly smiling John in her arms, she posing confidently with the look of an artist’s model of the twenties.

Then there she was in Paris, looking very chic, and in a group photograph in London with the Meninskys. ‘That’s Meninsky’s first wife – the one who ran away. I just don’t see how you can go off and leave two young children.’

A posed profile studio portrait puzzled me: it didn’t look like Sarah, but was familiar. ‘Is this Millie?’ I asked.

‘No, you daft thing, it’s me.’ (Sarah used schoolgirl language quite often: ‘You’re a real pal!’ ‘Don’t be so daft!’)

One photograph she found disturbing. ‘I’m not too sure about this one. I don’t remember it being taken,’ she said. It was a studio portrait of her young self, aged about thirteen. She was sitting on the floor, naked but for a strategic drape of fabric, her budding breasts exposed, her lovely head bent down, a thoughtful expression on her face. It was a beautiful study – one could imagine it featuring in an artistic photo magazine of the period: ‘Pensive’ perhaps, or ‘Girlhood’.

Presumably it was made by her father in the photographic workshop. This was not an uncommon pose: semi-nude very young girls feature in popular Edwardian art. But tastes have changed. ‘It’s lovely,’ I said.

‘Yes, but isn’t it a bit … don’t you think? I mean, what you read nowadays about paedophiles and child abuse.’ Frowning, she put it back in the box.

John returned and the afternoon came to an end. Several of the photographs were creased or torn, and I had told Sarah that it was easy for the local camera shop to restore them. After John’s death we found the box of photographs, all cleaned up, but the photograph of young Sarah was now one of only the enlarged head: Sarah had made away with the body.

Telephoning and walking

The telephone was placed in the hatch between the kitchen and the sitting room. When Sarah asked me to make a set of photographs of the kitchen for her friends, she especially asked for one which would show her talking on the phone, framed by the set of shelves which displayed china and casseroles.

She phoned frequently: it was an essential part of her life. She kept up contact in this way with her many friends, but she never spoke for very long. She had social skills of a very shrewd kind. Small gifts of fruit or vegetables would be left on one’s doorstep: a bag of mushrooms, some russet apples from the market. The doorbell would be rung and Sarah would be off – ‘You mustn’t outstay your welcome’ was one of her frequent sayings.

Walks across the park would be fixed by telephone, to meet at the fountain in the Broad Walk, an elaborate Victorian monument (given by a wealthy parsee) which John had featured in one of his poems. We would part at the Baker Street exit or at Great Portland Street, I this way, she that, each bent on her own affairs.

Sarah was often late, calling out apologies as she came down the path.

Whatever the weather she was happy to walk. In a biting wind she would shout, ‘It’s so invigorating!’ and as we looked up at the summer sky cry out, ‘Aren’t we lucky to live here!’

She would sometimes join Roberts in the park for his very early morning walk. Roberts himself became friendly with one of the park sweepers, who would greet regulars with a mixture of friendliness and deference so that they might imagine, Sarah said, that in the empty park they were walking in their own grounds.

Roberts was quite happy to speak to people whom he did not see as a threat, and was very touched when, on his last day before retirement, the park employee stood in a new corduroy suit at the gates to say a formal goodbye to the regular early birds.

In her late eighties walking became more of a problem, but she refused to give in, using a stick which became part of her personality, waving it to hail a taxi, flourishing it to make a point. But gradually her horizons narrowed, her walking became more limited – no more Hampstead Heath, no walking across the park; she took a bus.

The Roberts family were fiercely protective of Regent’s Park and Primrose Hill – Roberts had painted so many scenes of people enjoying the green spaces.

At one point there was a fashion for large, crude plastic sculptures, usually of popular figures, and some had been dotted about the park. Morecambe and Wise, two comedians, had been rendered in bright blue plastic suits and were sited near the flower gardens. John talked darkly of breaking into the park at night and blowing them up – ‘For which’, he said, ‘I would gladly go to prison.’

They asked me one day to come out with them, to help carry bags full of cardboard cartons. When we reached the statues, they began to decorate them with cereal boxes, empty packets, plastic bags. People stopped to look, laughing, and Sarah harangued them: didn’t they think that these hideous statues were an insult to the park?

Soon afterwards all the statues disappeared, and Sarah and John felt that they had contributed to their removal.

Liber Amoris and other tales

Sarah was a great admirer of William Hazlitt, and had handsome editions of his work, in particular of her favourite, the strange Liber Amoris, the account of his infatuation for his landlady’s daughter, a book of such a naked, confessional kind that it embarrassed his friends. It fascinated Sarah as a proof of one of her favourite sayings: ‘There’s nowt so queer as folk.’

‘I know the type,’ she would say. ‘I’ve lived in places like that and seen the lodging-house-keepers’ daughters, sly pussycats who sidle into the gentlemen lodgers’ rooms, willing to go so far and no further … But how he turns against her at the end, that’s not right. What does he call her? A lodging-house decoy, an impudent whore? By then he must have been crazed.’ She had more than one copy of the book which she had picked up over the years.

Much of her reading, aside from her own library, was haphazard, depending on the books John brought home with a view to reselling. She also picked up books at jumble sales – she had a sharp eye.

One day, discussing Hazlitt’s obsessive desire, she said, ‘You know, in a way it’s like that man Munby, the man who had a passion for working women and for servants, the dirtier the work they did the better. I’ve been reading his life – John brought it home the other day; I found it fascinating. And then there are those men who go for prostitutes, want their company. I could tell you a tale about that … Someone we knew well, he died suddenly, and was found together with two of them. Not nice for his wife. It was hushed up, as these things are.’

She was in a reminiscent mood.

‘Behind a lot of the paintings you see in a gallery there’s often a story – a story of how they got there by way of this and that. They’ve been from this person to that person, someone falls for someone maybe quite unsuitable, and paintings end up in strange hands.

‘I can tell you a tale – but don’t forget it’s my story: I’m keeping it for my memoir.

‘Well, it started when I was still living in Leeds. I used to go to a Lyons tea shop for the cream buns – they had very good cream buns in those days.

‘I got talking, as one does, to one of the young women working there. She had an interesting face, quite interesting – not exactly pretty, but there was something. So I introduced her to my brother Jacob, who was always looking for models, and he did some drawings of her. She sat for him a few times; I don’t think it went any further than that.

‘When I told her I was going up to London she said how much she envied me. She got my address from Jacob and wrote me a letter asking me to put her up for a few days.

‘Like a mug, I agreed. I felt sorry for her: it was such a dull life in that town, and she so wanted to see London – she’d never been away from Leeds.

‘She stayed with us in our flat in Fitzroy Street. You know the kind of place, a flat over a shop. There were two flats, but only one was supposed to be – what’s the word? – residential; ours on the top floor wasn’t meant to be lived in. She played me a dirty trick over that later on.

‘The man who had the flat below was a retired army captain, very much the retired military gentleman of the period, getting on in years.

‘He had artistic tastes, he collected pictures, and he’d bought quite a few from Bobby. He had a lot of good paintings he’d bought cheaply from artists who lived in the neighbourhood.

‘He had other tastes too. He liked little working-class girls, who he’d bring home, and he picked up housemaids, like that man Munby – you know the type.

‘One day, soon after she’d arrived, he saw our visitor walking up the stairs past his open door, and after that he was often to be seen standing by his door as she passed, with her modest look, little hat and short skirts. Within a week she’d moved in with him.

‘He was getting old, she was very determined, and eventually, shortly before his death, he married her. And there she was, a widow with some money, a fine collection of pictures, and an air she had acquired to go with it.

‘She went back on a visit to Leeds and went to see my brother, who introduced her to a local doctor who’d called on him at his studio. He was interested in art and was often there – and here was a well-dressed young widow who’d picked up a smattering of art-talk about her pictures. He fell for her, and she became his wife.

‘And later, when his career led elsewhere, she became Lady Whatnot.’

The dirty trick?

‘Oh, she told the authorities that the flat we lived in was being used for residential purposes and we were thrown out. I suppose she didn’t want us around when she was settling in with her elderly admirer. That must have been it.’

And later?

‘She died and her husband married again, someone or other. Then he died and his new wife inherited the paintings – I don’t know what’s happened to them. Such is life.

‘If Bobby had been a different sort of man – some sort of fashionable portrait painter, say – I might have been Lady Roberts. Not that I care, but sometimes I get fed up with friends who’ve married a title lording it over me. I invited two of them together to tea – you know who: you were there – and I told you then that once I’d introduced them they’d only talk to one another and so they did, completely ignoring my other guests. That’s the way of the world.’

That day, when I went home, I wrote up her Fitzroy Street story, just as she had suspected I might, and found it much later in an old notebook, wishing that I had written up many more.

No prying

She rarely spoke of the famous people she had known, and resented any questions leading that way. ‘Aha! You’re prying!’ she would say, or ‘I do dislike being treated like some sort of monument left over from the past. I like to live in the present.

‘People are on at me, want to interview me, tape-record me, but I’m not having it. What they want is to promote themselves.’

But sometimes she did speak unprompted of well-known people from her past.

‘As T. E. Lawrence once said to me – now there’s a conversational opening for you … ’ she began one day. She was discussing the David Lean film Lawrence of Arabia, which she and Roberts had disliked and were upset by, feeling that it presented a figure they did not recognise, so unlike the Lawrence they had known.

One anecdote she liked to tell to friends was of her meeting D. H. Lawrence. This varied slightly in the telling. To me she had described the encounter as beginning with an invitation to tea with Mark Gertler; Lawrence was the other guest.

Lawrence and Gertler had been sitting, she said, on either side of the gas fire in Gertler’s room, eating toast and drinking tea; it was a winter day.

‘I came in and I was introduced to Lawrence, but he took no notice of me at all – he had eyes only for Gertler. I was very annoyed, because in those days I was beautiful and used to attention, but then Gertler was beautiful too … ’

Once she spoke about Wyndham Lewis.

‘He used to come to his room, Bobby told me, before the war, and poke about among the paintings and drawings stacked along the wall, looking for ideas to pinch. He did that with other artists.’

‘What was he like when you knew him?’ I asked tentatively.

‘Very unpleasant.’

I grew bolder: ‘And Ezra Pound?’

‘Unspeakable.’

One day, discussing food, I asked what the food had been like at the Tour Eiffel restaurant, the setting of Roberts’s early-sixties painting of the Vorticist group. I thought this a safe question: she as well as Roberts must have eaten there often.

‘Delicious,’ she said. ‘Good French traditional dishes, properly cooked. Sad that he went bust, but he’d been too generous to the art crowd.’

She also proffered an anecdote of Augustus John: she was leaving in a taxi after a party, when John got in too and grabbed her. At the first red traffic light she disentangled herself and got out the other side. ‘It was a close shave,’ she said.

A curious glimpse of Aleister Crowley intrigued me. At one point, in the twenties, Sarah had been working for a Lady Somebody, as she called her, who was editing a magazine dealing with the occult. (Sarah was good at picking up odd jobs on obscure magazines, or in mysterious shops, and her interest in homeopathy led to many contacts on the fringes of the rational world.)

Calling at the house, she had been asked to go up to the bedroom, where her employer was still in bed. Seated at the dressing table was Aleister Crowley, in his Scottish mood, wearing a kilt; as he spoke he gazed complacently at himself in the mirror, she noticed.

‘So I’ve seen the Great Beast in person,’ said Sarah. She’d been reading about the current interest in Crowley and that he still had some sort of following, which she found surprising. Sarah was suspicious of all gurus, mystics, self-styled prophets, charismatic leaders.

Gurdjieff

One evening, at a party in my house, we were listening to my neighbour, the costume designer Sheila Jackson, telling us of her recent experiences in Paris designing costumes for a film to be directed by Peter Brook.

She knew Sarah from the days when Roberts was teaching at the Central School, where she had also taught (and she remembered that Roberts was called ‘Drainpipe Roberts’ by his students, referring to the tubular arms and legs of his painted people). Now she was discussing the subject of the projected film, Gurdjieff, a man whom Peter Brook believed had been a great teacher.

‘I’d designed at least three sets of costumes, everything kept changing; it was very confusing. At one point it was arranged that all of us working on the project should see a film of the great man, to sort of get us in the mood, I suppose.’

Sheila’s voice was brisk.

‘I went to scoff, but I have to say that I stayed to listen, and to my surprise I was most impressed. It completely changed my mind: he really had something to say. I could see why he influenced so many people.’

‘Well,’ said Sarah, ‘I saw him in the flesh – it was at the Conway Hall, I think. Like you I went to scoff, but I stayed to laugh. He was just another old humbug. There were so many around in the twenties.’

Bacon and breakfasting

When she joined Bobby in London she found that he was quite fussy about the quality of his breakfast bacon. For Sarah this – eating bacon – must have been a symbol of emancipation from the ritual Jewish traditions of her home, in addition to the thrill of living in sin.

When I first knew her, bacon was bought from Jacksons in Piccadilly, an old-established West End provision merchant. Roberts, on visits to the RA, would cross the road to the shop and buy the week’s supply.

He had a great admiration, Sarah told me, for one of the assistants who worked on the bacon counter, a slight, pale-faced, red-haired young man dedicated to his job, a quality appreciated by the hard-working artist.

Bacon was cut to order; if a side of bacon was not quite up to the standard needed for a certain thickness of slice, the serious young man would frown, shake his head, and go down to the basement for another, firmer, one. I too bought bacon from Jacksons, and was served by the same assistant. Once or twice I had to wait while he and Roberts were having a long chat, perhaps about bacon.

When Jacksons eventually closed, the young man moved a few doors along to Fortnum & Mason, but here the bacon was not cut to order but was sliced every morning before the shop opened and laid out on the counter: streaky, back, and so on. This did not suit the Robertses and it didn’t suit the young assistant – he seemed distraught, Sarah told me. Passing through the shop one day I looked for him at the counter, but he wasn’t there.

‘A funny chap,’ said a senior counter hand when I asked after the young man. ‘Had some sort of breakdown and left. Not coming back it seems.’

Well, here was someone to whom Roberts had regularly spoken.

One morning, earlier than usual, I called on Sarah and saw John eating a late breakfast at the small pedestal table in the bay window of the sitting room.

Outside there were the garden and the canal; the morning sun was streaming into the room, lighting up the marmalade in its jar, caressing the fat brown teapot, the cup and saucer, the milk jug, the crisp pink bacon on the plate. It looked like an illustration for a Victorian novel.

Roberts, an early riser, must have eaten his breakfasts here too, with the essential plate of egg and bacon to start the day’s work. Sarah was content with tea and toast in bed. ‘Ah, tea,’ she would say. ‘Nectar!’

Food: the desire and pursuit of the wholesome

One day, soon after William Roberts’s death, Sarah and John were surprised by a visit from his brother, not seen for many years. He had read of William’s death in a newspaper, he said. He looked, Sarah told me, disturbingly like Roberts himself in old age. They chatted, she served coffee, and she asked him how he, as a bachelor, coped with having to feed himself.

‘Tins,’ he said.

‘Just tins?’

‘Yes. You can get everything in tins these days. Meat, fish, vegetables, fruit, the lot. And they do an excellent rice pudding in a tin too.’

Telling me this Sarah said, ‘I felt so aggrieved. There he was, looking so healthy, living on tins, and Bobby dead. Why had I bothered all those years to cook fresh wholesome food? We could have lived just as well on tins.’

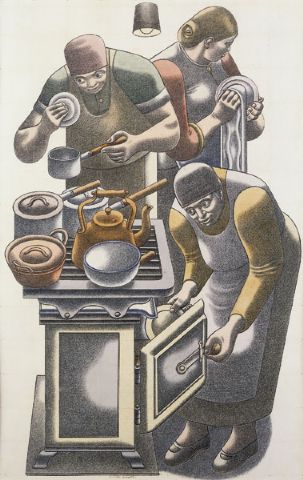

The Kitchen, 1942–5

Seeking fresh wholesome food, cooking well, even on a gas ring, a flirtation with health-food shops (here an obvious link with Roberts’s long-standing patron, Ernest Cooper, for whose health-food shops she wrote a recipe booklet), all this had taken much of her time.

When I knew her the pursuit of lovingly reared organically fed meat and poultry still needed dedication, as did the buying of fresh fruit and vegetables. An occasional visit to a supermarket would see her returning to hand back a ‘funny-tasting yoghurt’ or some rank butter. They must be putting stuff in the yoghurt, she thought, and the butter had been too long in storage ‘somewhere in the Common Market’.

‘How many hundreds, no, thousands of meals I must have cooked,’ she moaned to me one day when she was in her eighties. ‘I’m getting fed up. I’ll go anywhere for a meal if someone invites me. Whatever shall I cook tonight?’ This was a frequent question that she usually answered herself with ‘I know, I’ll cook savoury rice’ – this said with much emphasis: it was her standby.

Living in Primrose Hill, they seldom ate out, long gone the meals at the Tour Eiffel or Pagani’s or the cheap Soho restaurants of between the wars.

Roberts himself favoured tea shops, his favourite spot being the ABC café then still in Camden Town. Diana Gurney, a neighbour and friend of Sarah’s, remembers their sitting at neighbouring tables enjoying a cup of tea and a bun after they had both finished their teaching sessions at the Central School, each aware of the other but not speaking: rather, Diana said, preserving a companionable silence

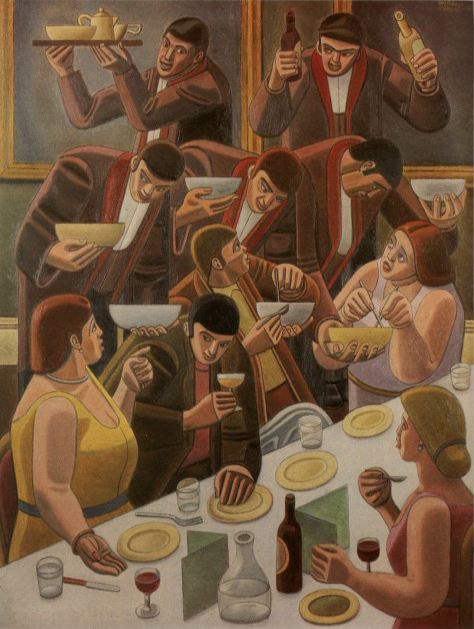

The Diners, 1968

But the Regent Fish Bar in Regent’s Park Road was an occasional evening stop for both Sarah and Roberts. The owner, Sarah said, would pick out the better pieces of fish to fry for them. Walking back home in the summer, they would make a detour via the well-known Marine Ices ice-cream parlour to buy cornets to eat on the way.

Sarah became very friendly with the mother of the Italian owners of Marine Ices, who, when she retired to their home town of Amalfi, urged Sarah to come and stay with her there. This was an offer Sarah never took up but liked to toy with. ‘Do you think I’d like it? she would ask. ‘Southern Italy? I’m not sure … but she’s very pressing. A week maybe?’

The Italian Trattoria Lucca in Parkway they had known since the days when it was a working-man’s caff, when La Signora served minestrone for two shillings and sixpence (parmesan cheese, sixpence extra); liver, bacon and chips, four and six; egg and chips, four shillings; jelly and cream, one and six – ‘Non e veramente crema, e crema di tin,’ as the owner was once heard telling some Italian friends she was entertaining there. ‘Those were the days,’ said Sarah. ‘We could get a cheap, decent enough supper there. Now that it’s all done up and serves fancy Italian food we don’t go there unless someone takes us.’ But she remained friendly with the handsome and hospitable Signora.

Very friendly too with the charming Chinese woman who greeted customers at her family’s restaurant on the other side of Parkway. The Phoenix Chinese Restaurant had been serving old-fashioned anglicised Chinese food for many years, though I never saw William Roberts there – perhaps he was wary of Chinese cooking.

‘You can see them buying vegetables in the market every day,’ John said. ‘That’s a good sign – fresh stuff. And the two of us can eat for under £15 – only £11 the other evening. Gives Sarah a break.’

‘She knows what I like,’ Sarah would say: ‘chicken and cashews. Always brings it to me without asking. And a soup. Such a nice little woman, I’ll be sorry when they retire.’

It was to be the place of Sarah’s last outing.

‘They went out for a Chinese,’ said a peremptory friend who was driving us back after Sarah’s funeral. ‘Two days before she died. Can you believe it? And she got up the next day to make a cup of coffee for a friend who’d called. I ask you!’

Once, long after Roberts’s death, we were formally invited to supper at St Mark’s Crescent. Sarah felt that she and John had accepted too many invitations to eat with us and some sort of return was needed. This was to be the only time we ate there in the evening. (As for myself, how many lunches had I eaten at the kitchen table, how many sitting-room teas!)

‘Do you like sprouts?’ was the question.

‘No. I hate them.’

‘Ah, but the way I cook them you’ll like them.’

We came in by the front door, were offered sherry in small glasses of assorted shapes, and then we sat at the kitchen table.

There were three small yellow Cousanges casseroles which were usually displayed on the shelves behind us – she had brought them back from a holiday in Provence in the thirties. Now she brought one to the table; in this she had cooked a delicious liver stew. In another casserole were the sprouts – sprouts which she had transformed into an edible vegetable, buttery, unsproutlike, as she had promised. In the third casserole, potatoes.

We had a steamed pudding she had made, and coffee in the Roberts’s style: freshly roasted beans from the nearby Delancey Street coffee-roasting shop, hand-ground, then brewed in a jug

How many good meals were served at that table; how well they ate, lucky William Roberts, lucky John.

I bought one of the yellow casseroles in the final sale of the left-over household goods at no. 14, the prices stipulated by the Treasury Solicitors – John had died intestate – so I paid £5 for a chipped sixty-year-old enamelled dish. But it is not just a memento of Sarah: everything I cook in it turns out well, as though she herself was supervising.

I haven’t tried to cook sprouts.

John the book man

From time to time I would be invited to lunch, after Roberts’s death, ‘to talk books to John’.

Lunch was sometimes a soup, always cheese, a wholemeal loaf and apples; water to drink. I would gruffly be asked what we had been buying, and hear what John had recently found. Paying between £5 and £10 for a book, he had stopped going to the big book fairs because he felt they didn’t want his custom. ‘I go to the smaller fairs – they’ve got more time to talk, different stock. Sarah and I have been going lately to one by Tower Hill – you can pick up some good things there.’

He collected books on London, nineteenth-century politicians’ memoirs, autobiographies written by actresses of the twenties and thirties, books on publishing, novels by Arnold Bennett, H. G. Wells, the tales of Ambrose Bierce. If he found a first edition of these writers he sold it and replaced it with a later one. It was very much a dealer’s library: he had once been a runner for a London bookshop.

I had given Sarah a set of Trevelyan’s history of the Italian Risorgimento, having bought a better copy; she had seen it lying about and asked me for it, knowing we never sold a duplicate.

‘She’s not going to read that,’ said John.

‘What do you mean?’ said an aggrieved Sarah. Later she told me that John had cheerfully sold it the same week. ‘He shouldn’t have done that. I told him so.’

Books bought for resale were stacked in a small bookcase near the door for visitors to inspect. Sarah once presented me with one she thought I might like. It was a collection of interviews with well-known women authors of the 1890s – well, once well-known: Frances Hodgson Burnett would be the only one remembered today. They were written in a style still popular: a mixture of fawning and impudence. I was fascinated. After a few weeks Sarah asked me for it back, then later gave it to me again, and again asked for it back.

John the spare man

After Roberts’s death Sarah and John were free to accept invitations as a couple. John’s lack of social grace was countered by the fact that he was that useful article a spare man. Sarah, who sparkled at a dinner or a party, was well aware of John’s lack of enthusiasm for what is called society. However, one lunchtime I found them arguing quite heatedly, Sarah berating him.

The evening before they had been invited to dinner by their friend known as Mouche, someone whom John respected as a woman of worthwhile achievement, a lecturer in dentistry and an amateur of music who was a music critic for Hampstead’s local journal, the Ham & High. They had originally met her at a concert.

But apparently that evening he had not spoken to anyone at her dinner party.

Mouche, Sarah said, was furious with him and declared she would never invite him again.

‘You said nothing at all to anyone the whole evening! When you’re invited out you have to sing for your supper. I do.’

‘Look, Sarah, be honest, was there anything said last night that was worth saying?’

‘Well, no, not really.’

‘Well then … ’

‘Music is a great solace.’

‘Music is a great solace as you grow older,’ Sarah had said to me when we first met, but music had always been part of the Robertses’ lives.

There were twenty-six guitars in the house, but Sarah never really mastered the playing of them and there are doubts about John’s skills, though he was a serious scholar of guitar history. No recorded music, but frequent concert-hall visits to hear chamber music – the Wigmore Hall the preferred venue for Sarah and Bobby. After Roberts’s death, Sarah told me that she would have a quiet weep whenever a favourite passage of his was playing in a quartet or other chamber-music piece.

The visits to the Wigmore came to a sudden end. None of the Robertses cared for contemporary music, and they objected to the sandwich type of programming in which a modern piece is placed between two classical works: they thought the modern piece should be played at the end, and let those who wished stay for it.

At one point John began to bring a book to read while waiting for the piece they disliked to finish.

He and Sarah would sit in the back row, and were well known as regulars. One evening the hall’s manager came to speak to John. ‘Mr Roberts,’ he said, ‘your custom of reading a book during a concert is disturbing for the public and the players.’

‘Well, I told him,’ said John to me, ‘the players can’t see me at the back – besides, they’re busy playing – and who exactly are the people who’ve complained? Were they sitting next to us? The people in front can’t see me, and no one in the back row has ever said anything to me.

‘The man had to agree with me: no one had actually come to him with a complaint – it was all his idea. Anyway, we’ve decided to give up the Wigmore and go to the Conway instead. It’s cheaper, and the players are younger, fresher too.’

So they became Conway Hall regulars.

Two sisters: Millie and Sarah

Millie and Leah, the two other Kramer sisters, had nothing of Sarah’s striking looks or Jacob’s dramatic appearance. Leah, who was what in those days was called ‘simple-minded’, was not able to live an independent life, whereas Millie – intelligent, sharp-faced and sharp-tongued – had made something of a business career in New York and at one point was considering marriage with a long-standing companion there.

But, said Sarah, Millie had always adored her brother Jacob. One of her happiest memories was his asking her to go with him to France when he made his portrait of Delius in 1932; Millie had taken charge of the trip. She had so wanted to be his companion, to be part of his life.

While Sarah as a young girl was his favourite model, portrayed again and again, there are only one or two Kramer portraits of Millie, and one notes that in the memorial book she put together for Jacob not one portrait of Sarah is reproduced.

When Jacob, after their mother’s death, asked Millie to come back to England to look after Leah she came at once, leaving her New York life for good. A terrible mistake, Sarah thought.

A small drawing of Leah by Roberts shows her sitting in a chair, in hat and coat, smiling vaguely. She was sweet-natured and placid, I was told, and, like Millie, a great walker. At weekends they criss-crossed England, staying at hostels on the way. It seemed a pleasant life.

When Leah’s sight failed, a place was found for her in the Jewish Home for the Blind on the south coast. Visited regularly by her sisters, she seemed content, Sarah thought.

After Jacob’s death Millie dedicated herself to producing a handsome memorial book, funding it from her savings, writing to everyone she could think of for contributions to the text, and was involved in the 1973 retrospective exhibition of Kramer’s work at the Parkin Gallery.

This was where I first met her, at the private view, smartly dressed, severe, a formidable defender of her brother’s reputation.

The next time I saw her was very different.

Sarah Millie’s keeper

Sarah asked me one day if I would go with her and John to visit Millie in Friern Barnet, the Victorian mental hospital in the north of London.

Living alone, fretting about Leah, who had died in the home for the blind, she had become subject to delusions of break-ins, of violence, had become very fearful, and her neighbours had alerted the Robertses.

It was the beginning of dementia, a condition Sarah refused to recognise, feeling that if only Millie – intelligent Millie – ‘pulled herself together’ after being in the hospital all would be well.

The great building was set among romantically beautiful grounds. We plodded up the long drive – John, whom at that time I hardly knew, silent.

Millie was sitting up in bed, flushed and feverish, alone in the ward. She began talking rapidly to John, telling him that he was her heir, she’d seen to it that there would be something for him.

I was touched by John’s tender response and soothing manner, patting her hand: ‘That’s all right, Millie, don’t worry your head about it. Just get better.’

Sarah was talking to the nurse in charge. It was a curious topic they were discussing.

I knew that Millie was a serious collector of Victoriana. She had a collection of parasols which Sarah gave to Leeds City Art Gallery after Millie died – later regretting she had done so – and of Victorian dolls. It seemed that she had asked for her favourite doll to have with her in the hospital – a surprising request. The nurse with whom Sarah was talking was very much against it, saying, ‘It would lead to regression. A great mistake. I say no, definitely.’

‘Funny,’ said Sarah on the way back: ‘when I asked my women friends what they thought they all said, “Oh give her the doll, let her have it.” But the men I ask say no.’

Millie never got her doll, and her collection was sold towards funding her care.

Once back at home Millie’s condition worsened, and Sarah had the idea of her changing her Wandsworth council flat for one in a sheltered housing complex for the aged near St Mark’s Crescent. By energetic attacks on bureaucratic councils she got her way. Millie’s Victorian furniture and bric-a-brac were transferred, and Millie was installed. Sarah would visit her every day. Perfect, she thought.

But after a short while Millie became more and more confused, causing problems for other residents, and Sarah was told that she had to leave, go into a home.

Now Sarah began the search for a suitable – and affordable – place, taking a different friend each time she viewed a possible one.

One day she asked if I would go with her, saying that other friends could bear no more; the shock of life at the end had reduced some to tears of misery.

‘I’m hoping you’re tougher,’ she said.

The places Sarah took me to were depressing: privately run, smelling of urine, a half-circle of the old sitting propped-up in chairs around a twittering television.

‘Why does it have to be like this?’ she asked. ‘Surely there’s a better way.’

One home which had accepted Millie was such a miserable place that Sarah and a helping friend removed her bodily, despite the aggressive attempts of the home’s owner to stop them.

In between homes, Millie was with the Robertses – no easy time for them.

A final home was selected. It was clean; it didn’t smell; Millie had her own room.

The problem now was money. How long would Millie’s own money last, and how to raise more?

‘Do you know what Bobby said last night?’ Sarah began. ‘He said, “If the worst comes to the worst we’ll have her here and look after her ourselves.” Isn’t that good of him? I was surprised, I must say: most men wouldn’t hear of it. It isn’t as if he doesn’t know what’s involved – we’ve had Millie with us between homes, rambling all over the house at night, doesn’t know where she is or what time it is.

‘And I must tell you, he’s given me his gold medal to sell for Millie.

‘Isn’t that nice of him?’

‘Buying and selling are two very different things.’

Selling Millie’s goods took some time.

Sarah had taken Jacob’s easel from the Wandsworth flat to put in the hall of no. 14, using it as a stand for sticks and umbrellas; John had taken the large Victorian sofa which had been in Jacob’s studio for his own sitting room; but many of the good nineteenth-century pieces Millie had collected had been taken to furnish her flat in the sheltered housing complex, which now had to be cleared.

Here Sarah called on Paddy Walker, an old friend who had an antique shop in Camden Town. He priced the items for her, and bought some of them for his shop. The money raised went to fund Millie’s stay in the various homes.

One piece proved hard to sell. This was a small, round rustic wooden table which Sarah said was a Welsh cottage table. ‘I’d like it for myself, but where to put it?’

It ended up in the space under the stairs, and there it stayed, home to baskets, pegs, gardening tools, even the oars for their boat, until it was resold in the general sale of the contents of no. 14 itself after John’s death.

Two other items for sale, Roberts’s RA gold medal and a small drawing by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, were rather different, one donated by Roberts himself, the other inherited by Millie. The small but imposing drawing of a reclining figure headed a letter addressed to Jacob.

‘Come with me when I sell them?’ Sarah asked. ‘You’ve never had to sell your stuff I suppose. It’ll be an eye-opener for you.’

It was.

I was struck by the rudeness of the people she approached, who must have known who she was, selling her husband’s inscribed gold medal. The man – it was always a man – sitting at the desk would hardly look up as she showed what she had to sell, then casually mutter a sum and look away again, intent on his papers.

‘Thank you very much,’ said Sarah each time, with dignity, and we went on our way. I was also surprised by the marked variation in the prices offered, but she said that was to be expected.

However, at Spink’s a charming young man, pink-cheeked and golden-haired, walked up to her and said, ‘Hello, Mrs Roberts.’ He offered the best price, and she clinched the deal. I had a vague idea that this might be a young Mr Spink, and certainly Spink’s dealt from time to time with Roberts’s watercolours so there may have been a connection.

‘Come with me again?’ Sarah asked another day. ‘It’s the Bond Street quarter for the Gaudier-Brzeska.’ She’d tucked it into a white envelope, and in the galleries she took it out to display it, explaining that the letter had been written to her brother Jacob Kramer.

She was treated as before, barely acknowledged by the person in charge, the price again varying markedly each time.

‘I’m tired, let’s have a coffee,’ she said after a few such encounters, and as we sat in a place off Bond Street she spoke to me about having had to sell items of jewellery, their books, their household goods all too often in the past, to pay the rent, to buy some food. ‘Buying and selling are two very different things. If I were buying you’d see how they’d make up to me. But that’s the way of the world.’

‘But at least one would expect common courtesy.’

‘Courtesy! Well … ’ And then she gave a cry. ‘I’ve lost it! Whatever shall I do? I must have dropped it! Whatever will Bobby and John say?’

She looked distraught. I suggested we go back the way we had come, retracing our steps – it wasn’t the sort of thing anyone would stoop to pick up, just an envelope.

We walked back along Bond Street, Sarah bewailing, our eyes on the ground, and there it was, trodden on by passing feet.

‘We’d better go straight home,’ said Sarah. ‘Promise me never to tell Bobby or John.’

She eventually sold the drawing for a fair price to a friend who owned a gallery of which she approved, who bought it as a present for her husband.

An outing

One afternoon she called on me to join her in taking Millie out to the park. It was a fine summer day, and the inhabitants of the home were in the garden, sitting on the terrace in the standard semicircle of chairs, blankly facing a small lawn.

‘I’ve come to take you out,’ she said to Millie. ‘We’re going to have tea in the rose garden.’

‘I want to go too!’ cried one old lady. ‘So do I!’ shouted another, standing up.

They were dressed in smart clothes, seemed well cared for and obviously well off – it was an expensive home. ‘Take me!’ cried another. ‘Me! Me!’ By now they were all shouting, one wetting herself in her excitement.

‘Oh, God, no! No! I can’t stand this!’ Sarah shouted, and she stamped her foot, clapped her hands.

‘Stop it! Stop it! Stop it! Shut up! I’ll come back and I’ll take you all out.’

Now they began to weep, like children, quietly, unhappily.

‘Quick, grab Millie and we’ll get out – the taxi’s waiting.’

The taxi driver was very understanding of Millie’s reluctance to enter or to leave the dark interior of the cab, of having to be coaxed in and out. ‘Take your time, the meter’s not on,’ he said.

Millie was able to enjoy the sunlit park, the roses, and her tea and cake, and was safely returned to the home.

‘It was a good cake,’ she said. ‘I’m a Yorkshirewoman and I know what a good cake is.’

‘Yes, you still know that,’ Sarah replied.

That Millie no longer knew how to write, or to speak coherently, or where she was or what time of day it was, Sarah found inexplicable.