AN ENGLISH CUBIST

PAULINE PAUCKER:

Sarah (1900–1992)

Illustrations © The Estate of John David Roberts. Text © Pauline Paucker, from the catalogue of the exhibition 'William Roberts and Jacob Kramer: The Tortoise and the Hare' (London: Ben Uri Gallery, 2003)

Cecilia, Millie and (on the right) Sarah Kramer

Sarah Roberts's childish face, vivid and confident, dominates one of the family photographs reproduced in Jacob Kramer: A Memorial Volume, compiled by the younger Kramer sister, Millie. [1] This striking vivacity and self-confidence, which stayed with Sarah into extreme old age, must have added to her attraction for the shy young artist William Roberts when they met in 1915.

She was born at the turn of the century, her Russian parents' first child in their new country. [Since this was first written, the 1911 England and Wales census returns have been published, in which Sarah is listed as born in 'Russia'. When the Kramer family arrived in the UK is unclear: they do not appear in the 1901 census, but Millie Kramer was born in Leeds in February 1904.] The family kept themselves apart from the other newly arrived immigrants – they were not village Jews: Max Kramer had studied painting in St Petersburg; Cecilia had sung in a travelling opera company in the Ukraine. They felt themselves to be different, despite their poverty. The children were made aware of the world of art and music.

Their father's work in a Leeds studio, painting portraits from photographs and retouching, brought in little money; hopes were fixed on the gifted son [Jacob Kramer], who, after his father's early death, tried to contribute to the support of his mother and sisters. Sarah had become a striking beauty: small but well proportioned and nicely rounded, she knew instinctively how to hold a pose. An ideal model, she sat for Jacob in the evenings when she should have been doing her school homework. His drawings of her dressed in fancy clothes, an Augustus John-style gypsy, were very saleable. A gallery in Bradford took them at half a guinea or even a guinea, which kept the family afloat for a while.

Sarah aged about 13

An early drawing of Sarah by her brother, Jacob Kramer

There was a vagueness about dates in Sarah's memories of this time: Jacob's going up to London to study at the Slade, her struggling to stay on at the grammar school, her desire to become a teacher, and Jacob's notion of her becoming an actress or a dancer. Uncertainty about her future was resolved when he took her to London to stay with David Bomberg and his wife in the school holidays. She was fifteen. 'He showed me off like a jewel,' she said. 'It was very embarrassing.' [2]

She was shown to William Roberts, Jacob's fellow student at the Slade, at a meeting in the ABC tea shop in Tottenham Court Road. Roberts was immediately struck. After joining the Army, he wrote to her from the front; and in 1918, now an official war artist, he sent for her to join him in London. She went to live with him in Percy Street – a daring thing to do, she thought. What would her mother think?

To Sarah's surprise, Cecilia welcomed Roberts into the family. It seemed that they liked one another, that she regarded Roberts as an honorary Jew. Jacob was not so pleased – he had lost a very useful model. John, the only child, was born in 1919; Sarah and William married in 1922. A lost double portrait of Sarah and her mother, Jewish Melody, now existing only in photographs, [3] was a tribute to his wife and to her mother, whom he painted more than once.

Jewish Melody, 1920–21

Oil on canvas, 160 cm x 90 cm (estimated size)

In one of the – rather scrappy – autobiographical notes which John asked her to write after Roberts's death, [4] Sarah said how very surprised she had been to see how compulsively Roberts worked at his easel each day, as long as the light lasted. This was in contrast to Jacob's careless and erratic ways, which she had thought were the mark of a true artist. (His nephew, John, wrote that Jacob needed conviviality, that he lacked the necessary ability to sit, solitary, at his easel for any length of time.)

How artists lived she well knew. One room in Albany Street served as studio and bedroom when John was small; Regent's Park was their drawing-room. They used the public baths; they constantly changed lodgings; cheques bounced; patrons paid grudgingly; possessions had to be sold when money was tight. 'That's love among the artists,' said Sarah.

Now she posed for her husband, who began the series of portraits of his wife which show her from her early twenties up to old age. Sarah took on the roles of model and mistress, muse and loyal wife, fervent supporter and promoter of Roberts's work, feeling strongly that any sacrifices she had to make were in the service of a fine artist – a great artist, she thought.

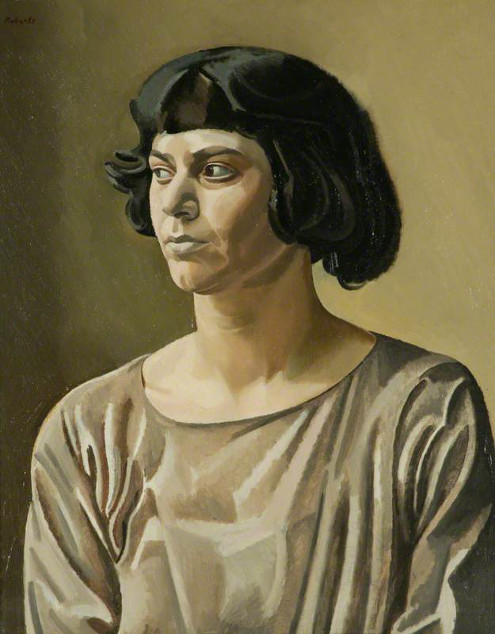

In his portraits of her ('He never flattered me,' she said) he often brought out her strength of character, as in the early portrait now in Manchester. [5] Here her gaze is stern, her jaw set with determination. This is the Sarah who asked the owner of the Leicester Galleries why, when they had an exhibition of her husband's paintings inside, there was no painting of his on show in the gallery window.

Sarah, 1922

Oil on canvas, 61 cm x 50.8 cm

She not only sat for portraits, she often posed for the figures in his busy compositions. All her gestures and actions, even when she was old, had a definite vigour and rightness – when hanging out washing, polishing a floor or scrubbing a kitchen table. They both had a D. H. Lawrence approach to domestic tasks, seeing them as serious rituals of daily life. (They knew and admired Lawrence; Sarah had an anecdote, which varied slightly with telling, of how she had first met him at tea with Mark Gertler.) When Roberts painted a mother bathing her son, a dressmaker pinning up fabric, women carpet-beating or cleaning the steps, it was surely Sarah who was the model or the inspiration for these scenes.

In hard times she found paying jobs. Between the wars she developed a network of people who would employ her: rich, artistically inclined women, publishers of mysterious journals, or people who dabbled in alternative medicine or health foods. (She wrote one of the small-format recipe books published for the health-food shops owned by Roberts's patron Ernest Cooper – a series with striking covers by Roberts, who also designed a calendar for Cooper's customers.) Her favourite saying was the Yorkshire 'There's nowt so queer as folk', and she collected a wide range of assorted types – who could also be useful.

She so much regretted having no creative talents: 'If I have a talent,' she said, 'it is a talent for living.' Which was true: each day was to be enjoyed. She also had the gift of making friends. Roberts became more and more withdrawn, but she, like her brother, needed companions.

As Roberts retreated from social life, speaking only to old friends and making no new ones, Sarah became his bridge to the world. If, when out together, they met a friend of hers, she stopped to talk and he walked on or, vaguely smiling, stood aside waiting for the conversation to end. At home, over their meals, she would amuse him with her day's adventures and 'sharp comments on her friends', as John put it. He needed no one else.

But there were two long-standing friendships in particular which made a big difference to their lives. She had known Sadie, the first wife of Ernest Cooper, for many years. It was surely her influence which led Cooper to invest in Roberts's paintings during the lean years when his work was hard to sell – and for Cooper it was to prove a profitable investment, as Sarah had foretold.

It was Victoria Kingsley, Sarah's close friend and a fellow student of the guitar, [6] who gave the Robertses the cash to buy their much loved house on the Regent's Canal, in exchange for some paintings. They had found themselves sole sitting tenants in what had been a rough rooming-house, but had not got the modest sum needed to buy the property when it was offered them. Victoria, living on inherited capital, had made a noble gesture. Owning 14 St Mark's Crescent gave her friends lifelong security. Neither Bomberg nor Gertler nor Wyndham Lewis ever had this kind of base – nor did Jacob Kramer, who lived and worked in rented rooms till the end.

The Robertses had originally furnished the ground-floor front room – rented after their return from wartime Oxford in 1946 – with a bed, an easel, a table and two chairs. This room afterwards became Roberts's permanent studio, a holy place, where he was not to be disturbed. Sarah's realm was the basement sitting-room, kitchen and garden; their son, John, was given the top floors. John had left a career in physics for life as a poet and guitarist; his father had illustrated his first two books of poetry, privately published during the war, [7] though Roberts did not find it easy to understand his son, whose attitude to work was not his.

The routine of the house was arranged around Roberts's working day, with regular, well-cooked meals (Sarah was an excellent cook) and daily walks in Regent's Park or on Primrose Hill. Sarah, who liked to entertain, was limited to tea parties, but guests had to be gone by six o'clock, when 'Bobby' – as he was called by his wife and son – clumped down the stairs to the sitting-room. No guests were to call unannounced, and all were desired to enter by the side door, to avoid passing the studio.

Did she find her life restricted? Certainly after Roberts's death she enjoyed her years of freedom and travel, shared with John. She sometimes wistfully thought that had her husband been a different character – a Sir John Lavery, say – he might have been knighted, there would have been elegant, flattering portraits of her as a fashionable beauty, she would have been Lady Roberts, socially on a level with those of her pretty friends who had cast aside love among the artists for marriage to a successful businessman. This fantasy would sometimes be raised, but would quickly be dismissed. She did not regret her choice.

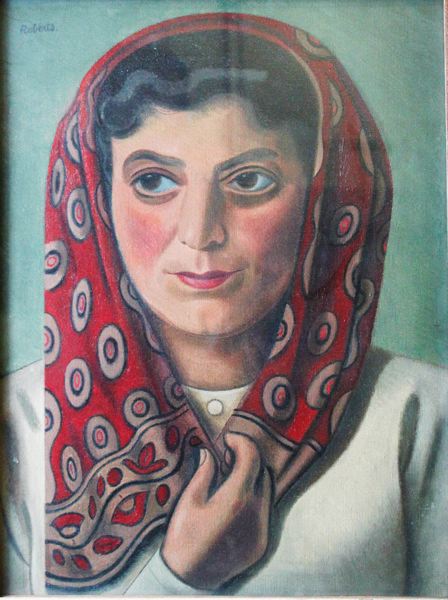

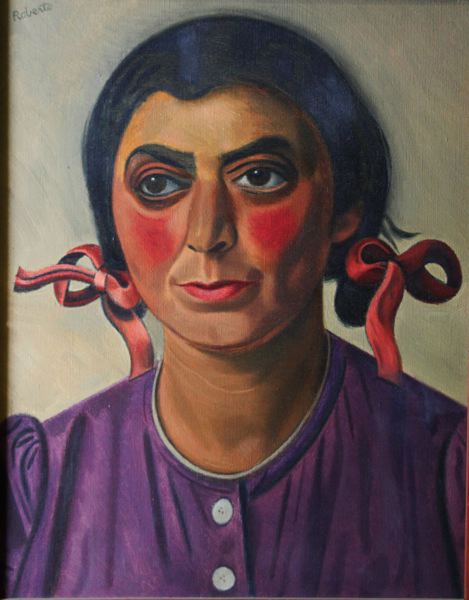

She could point to portraits of herself in the Royal Academy summer exhibitions, where Roberts latterly showed his work. (As an Royal Academician he could sell a certain number of paintings without paying the gallery commission he so resented.) He continued to paint her even as she grew old, saying that he needed no new young models: for him her face changed constantly and was always full of interest. He painted her in the patterned headscarves he liked – with black hair and pink cheeks she was a Russian peasant; with her hair tied in coloured ribbons she became a red-cheeked Russian doll. [8]

Sarah with Headscarf, c.1935

Oil on canvas, 43.5 cm x 33.3 cm

La Gitana (aka Sarah with Her Hair in Ribbons – Reading 1983 – and Sarah in Roberts, Paintings and Drawings 1909 –1964), 1948–9

Oil on canvas, 50.8 cm x 40.6 cm

A Sarah can be seen among the voracious women of The Temptation of Saint Anthony. A long, striped scarf turns her into L'Algérienne. [9] For earlier portraits she had often worn colourful clothes she had made herself or dramatic self-trimmed hats, to great effect. In the introduction to one catalogue she even describes having made a brightly coloured tie for one of Roberts's self-portraits.

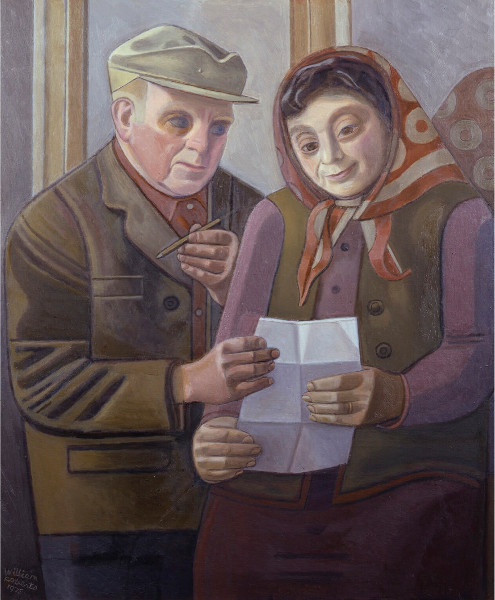

The double portraits are very touching. The one painted in Oxford in 1942 has an anxious, worried feel, no doubt due to the times; the painting of 1975, when he was eighty, she seventy-five, is very tender. With what care he paints her large eyes, with their unusually heavy upper and lower lids, contrasting with his own round, pale-blue eyes in a darkly red face.

The Artist and His Wife, 1942–3

Oil on canvas, 61 cm x 50.8 cm

The Artist and His Wife, 1975

Oil on canvas, 76.2 cm x 64.2 cm

When she was a bright-eyed old lady, her beauty gone, she would play the eccentric, even the clown, to get what she wanted. Underneath was a shrewd judge of character, dispenser of sound advice. Her quiet persistence was responsible for the National Portrait Gallery's 1984 exhibition 'William Roberts 1895–1980: An Artist and his Family'. Most of the pictures came from the Roberts's own collection. [10]

At that time, seeing her life in portraits led Sarah into a reminiscent mood, more responsive to her friends' queries about the past. She usually disliked being asked about the outstanding people she had known; she felt she was being treated as a monument. For her the present was more important. But she sometimes spoke of T. E. Lawrence, whom she had very much liked, and sometimes she would tell anecdotes – not to his credit – of Wyndham Lewis. Ezra Pound, she conveyed, was unspeakable.

Her reminiscences included memories of Rudolf Stulik's Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel in Percy Street, and how very good the food had been – and of Stulik's bankruptcy, when the mural panels Roberts had painted for him sold so cheaply at the auction and they had no money to buy them. [11] She talked about Gertler and Bomberg, dogged by poverty just as she and Roberts were. 'It's terrible', she said, 'when a borrowed half a crown makes all the difference. It can end a friendship.' It was only in the 1970s, when Roberts's paintings were selling at fair prices, that she told John, 'We don't have to worry about money any more!' Her role in later life had extended from 'muse' to the promotion and sale of Roberts's work as he retreated from contact with the art world. She took on the negotiations with buyers and galleries, and in her mid-eighties she handed the agency over to John.

They saw their task as protecting Roberts's reputation, thinking that he had not been given his rightful place among the artists of his generation. They jealously guarded material, with the idea of John writing his father's biography, and they took over Roberts's suspicious attitude to art historians and art critics. Their dream was that 14 St Mark's Crescent would be a house museum dedicated to him: this they thought would widen his appeal, find him a new public.

With this aim they had kept a variety of his work and had even bought back some paintings, while continuing to sell just enough pieces selected from their store to live on. They were frugal, and needed little. The house – with doors, cupboards and kitchen dressers carpentered by Roberts himself – was furnished with a Shaker-like elegance and simplicity. It was a perfect setting for the display of his paintings in the rooms they lived in, with a special display in his studio, where his easels and palette were kept as he had left them. [12]

All three died at home, but John's dying intestate scotched all idea of a museum, though a group of friends tried hard to achieve it. As for Sarah, she had once said, 'I shall go out like a light' – as indeed she did, rising from her bed to make a cup of coffee for a friend on the last day of her life, and dying quietly in the small hours.

Slight the farewell that she took,

my mother, she just ceased to live.

Without one word or backward look,

we were not so demonstrative.

John David Roberts, from Poems for Sarah (2003)

[1] This book was devised and put together by Millie Kramer, who published it at her own expense in 1969. It is interesting that she included none of Kramer's portraits of Sarah.

[2] Much of the information in this piece comes from Sarah Roberts's conversations with the writer over a number of years.

[3] Reproduced in the catalogue of work Paintings 1917-1958 by William Roberts ARA (London: 'A Canale Publication', 1960), pp. 22–3.

[4] These notes, intended by John for a planned biography of his father, are among the material currently held in trust in the Tate Gallery archives.

[5] Sarah, 1922. City of Manchester Art Galleries.

[6] Both Sarah and John were keen guitar players. Roberts painted a lively portrait of John instructing his mother.

[7] [John] David Roberts, Four Fables, with designs by William Roberts (Oxford: Joseph Vincent, 1942), and [John] David Roberts, Fantasy for Flute (Oxford: Vincent, n.d.).

[8] These two portraits, owned by the Roberts family, are currently held in trust by the Tate Gallery.

[9] The Temptation of Saint Anthony (1950) and L'Algérienne (1962) are owned by the Tate Gallery.

[10] The poster advertising this exhibition reproduced the 1975 double portrait, bought by the National Portrait Gallery.

[11] Two panels survive: The Diners, owned by the Tate Gallery, and The Dancers, owned by the Glasgow Art Gallery. Both were painted in 1919.

[12] A photographic record of the interior of the house is held by the National Monuments Record, the public archive of English Heritage, and by the William Roberts Society.

Home page | Chronology | Bibliography | Collections | Exhibitions

News | Gallery | Auction results | The artist's house | Contact

List of works illustrated on the site

Catalogue raisonné:

chronological | alphabetical