AN ENGLISH CUBIST

TIM CRAVEN:

William Roberts, The Revolt in the Desert

Illustration © The Estate of John David Roberts. Text © Tim Craven, from the January 2012 William Roberts Society Newsletter

The Revolt in the Desert, 1952

Oil on canvas, 240 cm x 145 cm

Southampton City Art Gallery purchased William Roberts's The Revolt in the Desert through the F. W. Smith Bequest Fund in 1958, for £750. The previous owner was Roberts's friend and patron Ernest Cooper, of Lindfield, Sussex. Roberts's watercolour The Travelling Cradle was acquired at the same time through the same means, though from the Leicester Galleries.

A 1995 letter from Cooper (aged 85) to the gallery states that he bought The Revolt in the Desert from the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in 1952 for £250, and that John Rothenstein borrowed it to show at the Tate Gallery for a whole year. He wrote that Maurice Palmer, Southampton's curator from 1950 to 1970, had kindly housed about 24 of Roberts's works that Cooper owned but no longer had the space to display when he moved to London. With the proceeds of the Southampton sale ('You could do a lot with £500 in those days'), Cooper and his first wife, Sadie, took Roberts and his wife, Sarah, on a trip to Greece, having just seen a memorable performance of Berlioz's The Trojans at Covent Garden together: 'I had the wild idea that "Bobby" would do a painting to match it. In the event his chief wish in Athens was to find a substitute for the Joe Lyons Corner Houses which were our favourite meeting places.'

T. E. Lawrence – the subject of The Revolt in the Desert – had admired Roberts's work and invited him along with other artists, including fellow Vorticist Edward Wadsworth, to illustrate his epic account of his role in the Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, published by subscription in 1926. Robert's Camel March was composed with the help of photographs lent to him by Lawrence to help with the details. Lawrence was delighted with the results: 'It's a trifle . . . but the technique of dress, shapes of camels, seats of riders etc. are as right as if you had worked them up on the spot. I'm afraid that means that you have exhausted yourself in continual study of those photographs. However I'm enormously grateful.'

The legend of 'Lawrence of Arabia' began to grow when details of his exploits became known after the war, and in August 1922 Lawrence astonished friends and critics alike by joining the Royal Air Force at the lowliest rank and under an assumed name to escape press harassment. The struggles of a less than fit, over-age Aircraftman John Hume Ross to cope with the rigours of the RAF's training camp at Uxbridge gave him the subject for his second book, The Mint. It is so full of parade-ground, blasphemous language that it was not printed in an unexpurgated edition until the 1970s. In 1922 Roberts painted a strong but sympathetic portrait (now in the Ashmolean Museum) of Lawrence posing as Ross in his new RAF uniform. The portrait suggests that Roberts liked and respected Lawrence without regard to his reputation.

Lawrence was to die in a motorcycle accident in 1935, but The Revolt in the Desert clearly shows that Roberts's deep admiration for him persisted, as this magnificent tribute was not painted until 1952. Lawrence – his identity made clear by his gold dagger and blue eyes – is depicted at bottom right, accompanied by a party of Bedouin tribesmen, some on foot and others mounted on camels.

This extraordinary work is often on display at Southampton City Art Gallery, and is much loved by regular visitors.

In his pamphlet Early Years, written in September 1977 and published posthumously in 1982, William Roberts summarised his relations with T. E. Lawrence as follows: 'In 1920 Colin Gill, who had been a fellow-student at the Slade, sent me a note saying "Colonel Lawrence is seeking artists to make portrait drawings for a book he is producing; get in touch with him." I wrote to Lawrence and as a result I contributed several portrait drawings to "Seven Pillars of Wisdom", besides a painting of Lawrence in his Royal Air Force uniform. He sat for this portrait in a room I was using at Coleherne Terrace, Earl's Court . . . He lent me during several Summers his small woodman's cottage at Clouds Hill in Dorset.'

Lawrence was delighted by the Seven Pillars portraits – for example describing that of Sir Henry McMahon as 'absolutely splendid: the strength of it, and the life: it feels as though at any moment there might be a crash in the paper and the thing start out', and that of Captain Robin Buxton as 'astonishing . . . A wonderful drawing' – and Roberts went on to produce other illustrations for the book, notably Camel March, mentioned above, and 29 tailpiece drawings.

Several of the tailpiece drawings are now in the Houghton Library at Harvard University, along with studies for them and others that were eventually not used, and some of the studies offer a fairly rare chance to see Roberts's very early ideas for a picture, before the familiar stage of a meticulous pencil study squared up for development as a watercolour and in some cases as an oil too.

The room in Earl's Court in which the portrait of Lawrence was painted was rented from the wood-engraver William McCance, copies of whose correspondence with WR about a bounced cheque for the rent are in the Tate archive.

Also in the Tate archive is a curious note by Roberts's son, John:

My father had a proof copy of 'Seven Pillars' with the annotations of Lawrence, who passed it to him by sections, as finished with so that he could design tailpieces. Later WR had a note from the Foreign Office about it, and he went down and waited in a corridor with it. Someone came out and examined it, but said it was of little value. Sarah took it to [book dealer Bertram] Rota, who gave her £20. 'We had to have the money.' But WR was not trying to sell it to the FO.

The FO's interest in the proofs may have been just bibliographic, but it is known that there was some official unease about Lawrence after he denounced what he saw as Britain's eventual betrayal of the Arab cause.

Lawrence knew that the Robertses had no money, and was kind enough to offer Clouds Hill to them for summer holidays. He would look in from time to time to see how they were getting on. They were probably too polite to complain about the sanitation, which consisted of a bucket, the contents of which the guest was expected to dispose of around the four acres that went with the property. Another note by John in the Tate archive states, 'Our last stay took many weeks of a fine summer . . . WR dug a latrine, army fashion, up the hill among the rhododendrons. I have wondered since whether L. approved.'

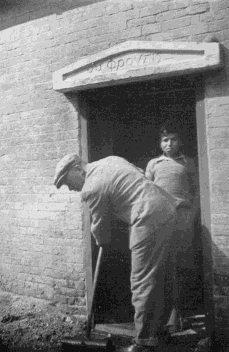

William and John Roberts at Clouds Hill

in the early 1930s

Home page | Chronology | Bibliography | Collections | Exhibitions

News | Gallery | Auction results | The artist’s house | Contact

List of works illustrated on the site

Catalogue raisonné:

chronological | alphabetical