AN ENGLISH CUBIST

WILLIAM ROBERTS:

A Press View

at the Tate Gallery

[Vortex Pamphlet No. 3]

For the context in which this pamphlet was published, see John David Roberts, 'A Brief Discussion of the Vortex Pamphlets'. The ellipses in the text are Roberts's own. Text and illustrations © The Estate of John David Roberts.

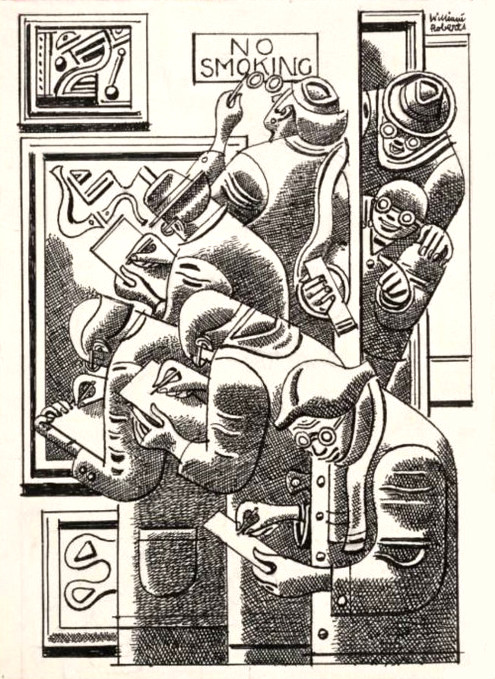

Cover and frontispiece for Vortex Pamphlet No. 3

THE CRITICS CRITICISED

Wyndham Lewis, aided by Sir John Rothenstein, The Arts Council, and some Pardners, Buddies and Pals of the Press, is making a bid to establish himself as the sole originator of abstract painting in England.

It is not only a question of the vanity of an artist that is here involved, but Art Economics as well. Finance plays its part, for if Lewis can be shown to be the first abstract painter in England, from whom the others have stemmed, then 'holders' of Lewis stock will find their shares rise in value on the world Art Market: the slogan is 'Knock out your early Competitors'. Following the large exhibition of his pictures at the Tate, to which had been attached some slight examples of the work of other artists, ostensibly his 'Followers', this collection, sponsored now by the Arts Council, is off to visit Manchester, Glasgow, Bristol and Leeds. In connection with this exhibition, misnamed 'Wyndham Lewis and Vorticism', it is interesting to see how the critics have supported this claim to supremacy in 1914 by Lewis and his 'Backers'.

First there was Sir John's appeals in The Times asking for information of the whereabouts of any works by the Followers or, if you prefer it, Other Vorticists. Artists, it is true, sometimes advertise for pupils, but advertising for Disciples, that is surely something new in Art.

However, Sir John was determined that Lewis should have every chance of showing the public the 'Effect of his Impact upon his Contemporaries', even if it meant turning the Tate into a kind of bureau of missing persons.

Then we have The Listener. Mr. Clutton-Brock is an Art critic; in this capacity he has paid a visit to 'Wyndham Lewis and Vorticism' and forthwith proceeds to tell his listeners all about it.

To begin with, he quickly disposes of that additional portion of the exhibition that consists of minor examples of the work of Nevinson, Wadsworth, McKnight-Kauffer, Dobson, Bomberg and Kramer, with the remark, 'SOME OTHER ADHERENTS, SOME OF THEM NOW LITTLE KNOWN, OF THE VORTICIST MOVEMENT'. I would like to point out that only one of the artists mentioned (Wadsworth) had any connection with Vorticism.

With a sigh of relief, Mr. Clutton-Brock is now ready for the main dish – this 'Most welcome exhibition of Wyndham Lewis's work'. Lewis, he finds, is 'As much as Picasso the creator of a world', who expresses himself in his painting in 'Abrupt and startingly original statements'. Lewis, it seems, has also for our critic another startingly original quality, that of being able to remove from the work of other artists who come in contact with him, any individual character and ideas of their own. We have seen at the start how, in the opinion of our critic, Lewis's co-exhibitors at the Tate have dwindled into 'Adherents', some of them now little known, of the Vorticist movement. Now, in conclusion, it is my turn to undergo this specialised Lewis-Patent-Artistic-Reputations-Reducing-Process.

Thus . . . 'For all the idiosyncrasy of his art the style of his invention could be profitably modified by other artists, as may be seen in one of the best of all Mr. William Roberts' paintings, 'The Cinema'.

One perceives the innuendo here: 'The Cinema' is the best of all my paintings for Mr. Clutton-Brock because I have had the help of the 'Style of Lewis's invention', have profitably modified the 'Style of his invention'.

I must confess it is not clear to me from the wording who got the profit as the result of this piece of pictorial legerdemain. Was it my painting, or was it Lewis's style that profited? It certainly was not me personally, for the picture went cheaply.

Obviously it is very risky today for any artist disposed to a clear and precise expression of form and an inclination to abstract treatment in his painting, to have his work hung in the vicinity of a picture by Mr. Lewis, for in this case he is more likely than not to be dubbed an 'Adherent' by some partisan critic. Mr. Clutton-Brock has been so moved by the Vorticistical-Æsthetical incantations of Lewis that he is willing to grant him the sole monopoly of all straight lines, angles of every description, not to mention curves, circles and ellipses. Yes, in the opinion of our critic, Wyndham, impressive in his Vorticist regalia, has cornered the entire home market in geometric forms.

Then we come to the article in The Times of 6th July, from which I give two extracts. No. 1 . . . 'It seems hard to believe that as early as 1912 English painting had in its midst an artist whose work and whose unequivocally articulate theory were as early an expression as any in Europe of the main principles on which the revolution in the art of our times has been based. Mr. Wyndham Lewis was producing entirely abstract drawings at a time when perhaps only Kandinsky had done so before him.' Well, it seems even harder to believe that this critic could pass over in silence names such as Picasso, Braque, Gleizes, Leger and Delauney, artists whose revolutionary cubistic paintings had been produced in France from 1906 down to 1912. To this Times critic it appears there was little doing in art upon the Continent in 1912. Except for a single, solitary Russian in Munich named Kandinsky, who 'perhaps' was doing a little abstract painting, things were very quiet indeed.

But not so in London, however, for it was here that the 'Unequivocally Articulate' revolutionary theory of abstract art was taking shape. Whatever doubts this critic may have regarding Kandinsky's contribution, there is certainly no 'perhaps' in his mind when he speaks of the achievements in abstract art which he attributes to Wyndham Lewis at this period. It appears the state of affairs in London Art circles was dull, too, around 1912. Lewis seems to have been as solitary a figure in London as Kandinsky in Munich, if we are to believe The Times.

Clearly this critic is little versed in the art history of those years, for the names of Epstein, Nevinson, Wadsworth, Roberts and Bomberg, all abstract artists contemporary with Lewis, seem unknown to him, which easily explains, of course, the astonished admiration he displays over the early work of P. W. Lewis. The character of Lewis's work at this stage is, in large measure, the result of the 'Immediate Impact' of French Cubism. Furthermore, he did not jump with a ready-made bundle of 'Unequivocally Articulate' theories out of nowhere.

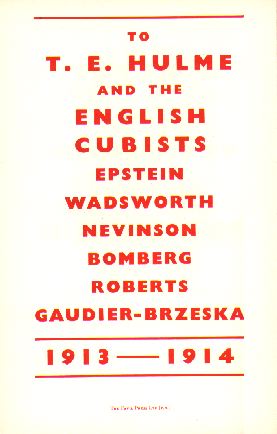

In this matter of 'Theories' we must not leave out of account three of his predecessors – Roger Fry, Marinetti and T. E. Hulme. In art history, as in history generally, even 'original' talents do not develop in a social vacuum. From this rule, Mr. Critic, no exception is made for SuperVorticists.

Times extract No. 2 . . . 'The Tate has found room to include a small representative selection of the work done by those artists who were professed followers, or who came under the immediate influence of the Vorticist movement.'

Well! well! 'Professed Followers' and 'Under the Immediate Influence'. Speaking for myself, I have never met a 'Professed Follower', a really self-confessed follower of Lewis. On the other hand, I could name quite a few 'Professed Opponents'. This 'Following' and 'Under the Influence' stuff is language more appropriate to Bow Street than the Tate Gallery. Just imagine it, sentenced by the Chief Magistrate of Art, sitting with a partial jury of Art critics, to six weeks' hard at the Tate for being 'Professed Followers'. Phew! what a 'stretch'!

The following nosegay culled from the pages of the Times, Listener, New Statesman and Tate Gallery Catalogue, will emphasise my point: 'Professed Followers' and 'Under the Immediate Influence' showing the 'Effect of the Immediate Impact' . . . 'Adherents, some of them now little known, of the Vorticist Movement' . . . 'Who have profitably modified Lewis's style' and, finally, 'Look like a lot of sprats a whale has caught'.

Nice work, boys! Whilst glorifying the 1956 Lewis, this is what his Press Buddies at the same time bestow upon the Cubist painters, his contemporaries of 1914.

T. E. Hulme, in an article on David Bomberg in The New Age for July 1914, writes: 'Mr. Bomberg stands somewhat apart from the other English Cubists. I noticed that in signing a collective protest published a few weeks ago, he added a footnote, that he had nothing whatever to do with 'The Rebel Art Centre' (Lewis) . . . very wisely in my opinion'. This is more than an opinion: it is a prophesy! Thanks to Lewis, Rothenstein, and the civil servants at the Tate, the Independant of 1914 becomes the Adherent of 1956.

With regard to the claim made by the critic of The Times, that in 1912 'Mr. Lewis was producing entirely abstract drawings at a time when perhaps only Kandinsky had done so before him', the following data may be of interest. In 1906, beginning of Cubism with Picasso's painting, 'Demoiselles D'Avignon'; 1908, Picasso, 'Deux Femmes Nues' (Cubist); 1909, Picasso, 'Femme à la Guitar' (Cubist). These years, down to 1912, teem with the productions of abstract painters such as Braque, Delauney, Gleizes, Metzinger, Leger, Juan Gris and a score of others, Italian as well as French. Especially important is the year 1910, with Marinetti's Futurist Manifesto published in Milan, and Roger Fry's First Post-Impressionist exhibition held in London, which introduced Cubism into England. Only a year before this, and three years after Picasso's 'Demoiselles D'Avignon', what do we find the man with the 'Revolutionary Art Theory as early as any in Europe' doing? Copying Franz Hals in Holland and Goya in Spain!

The following chronology will help to clarify the position of the various artists concerned during the years immediately following Roger Fry's first Post-Impressionist exhibition and the part I played in the start of the Cubist Movement in England.

Born in London, 5th June, 1895.

1909, Studied at St. Martin's School of Art as an evening student.

October 1910 to June 1913, Student at Slade School of Art. Had as fellow students, Wadsworth, Nevinson, Bomberg, Gertler, Paul Nash, Stanley Spencer, Ben Nicholson. At the Slade we were all familiar with the work of the French Cubists. Left the Slade at the age of 18 years and began to paint in the Cubist manner. Works of this period include 'The Dancers', 'Religion', 'The Prisoner'. In summer of 1913 joined Roger Fry's Omega Workshop and exhibited as a member of his Grafton Group at the Alpine Club Gallery.

1914, Join the newly formed London Group and showed a number of pictures at their first exhibition at the Goupil Gallery. It was about this time that I made the acquaintance of Lewis. The fact that I was at the Omega made him curious to meet me, for he, too, had worked there. One day he called upon me where I lived in Cumberland Market and borrowed a painting ('Dancers') and a drawing ('Religion') to exhibit at the Rebel Art Centre. The 'Centre' consisted of two rooms on the first floor of an old Georgian house in Great Ormonde Street, Bloomsbury. Sir John Rothenstein, endeavouring to reconstruct with the help of his imagination the 1914 scene, supposes that I met T. E. Hulme there, but he errs enormously in this. I visited the Rebel Art Centre only once and stayed about five minutes. On this one occasion, besides Lewis, I saw there only a lady I knew as 'The Countess'; she was not an art student, revolutionary or otherwise. Upon Hulme there is also little to be said. I remember walking with him and Ashley Dukes late one night along Charing Cross Road homeward from the Café Royal; the conversation during this brief walk was not upon philosophy. Sir John, who in 1914 was 13 years old and still at high school, gets his knowledge of this period from his friend and adviser Percy Wyndham Lewis. It was some months after this visit to the Centre that I saw Lewis again. He called on me with a copy of the first 'Blast', in which were reproduced the two pictures I had lent him for his Rebel Centre. Thus began the 'Vorticist Dodge'.

1915, Sent several works to second London Group show at the Goupil Gallery, among them a large Cubist painting, 'Boating'. About this time had reproduced in the Evening News a drawing entitled 'A Futurist St. George'.

Contributed two Cubist drawings and also several paintings, among them the 'Draughts Players', to the further activities of the Vorticist Racket, i.e., the second 'Blast' and the Doré Gallery show. This was my last appearance in 'Vorticism' until, in 1956, the Farce was revived at the Tate under the management of Sir John Rothenstein with Wyndham Lewis cast for the Lead.

1916, End of my Cubist phase and the commencement in March of that year of my war service.

With regard to the origins of abstract art in England, the evidence contained in the weekly numbers of The New Age, ranging from December 1913 to July 1914, is decisive, for it proves that there was in England a group of Cubist and Abstract artists working and exhibiting independently of Lewis before the word Vorticism was introduced. One realises today that this word was intended to be a kind of Trade-Mark, to secure for Lewis, its patentee, a monopoly over the Cubist movement in England.

The journalist T. E. Hulme, who championed the English brand of abstract art, contributed a number of articles to this paper upon those artists who were working in the Cubist manner at that time. These articles were illustrated with reproductions and bore the title 'Contemporary Drawings'.

25th December, 1913. Jacob Epstein (drawing), 'The Rock Drill'.

15th January, 1914. Review by T. E. Hulme of the Grafton Group at the Alpine Club Gallery mentions 'No. 29', a very interesting pattern by Mr. Roberts.

19th March, 1914. A drawing by Gaudier-Brzeska, 'A Dancer'. Also review by Hulme of the first London Group exhibition: mentions Bomberg, Epstein, Lewis and other artists.

2nd April, 1914. Drawing by David Bomberg, 'Chinnereth'. Announcement by Hulme of a series of drawings by Bomberg, Gaudier-Brzeska, Epstein, Hamilton, Nevinson, Roberts and Wadsworth, to be published in The New Age. It will be noticed that Lewis's name is not on the list.

16th April, 1914. Drawing by William Roberts, 'A Study'.

30th April, 1914. Two drawings, 'The Chauffeur' by C. R. W. Nevinson, and the 'Farm Yard' by Edward Wadsworth.

7th May, 1914. F. T. Marinetti's Futurist Manifesto, 'Geometric and Mechanical Splendour, in words at Liberty. Translated by Arundel del Re'.

18th June, 1914. Account of a lecture given by C. R. W. Nevinson at the Doré Gallery on Futurism.

9th July, 1914. Review by T. E. Hulme of a one-man exhibition at the old Chenil Gallery of Cubist work by David Bomberg. Hulme begins his article with these words: 'Mr. Bomberg stands somewhat apart from the other English Cubists. I noticed that in signing a collective protest published a few weeks ago, he added a footnote that he had nothing whatever to do with the Rebel Art Centre . . . very wisely in my opinion.'

(The Rebel Art Centre was started by Lewis in opposition to Roger Fry's Omega Workshop.)

16th July, 1914. Translation of an article by the theoretician of Futurism, the Italian F. T. Marinetti, entitled 'Abstract Onomatopoeia and Numeric Sensibility'.

This was the last number of The New Age to concern itself with the affairs of the English Cubists. The 4th of August was but a few days off: soon the Battle of Mons, with its heroes and angels, was to be front-page news.

It will be clearly seen from the foregoing that much had been done and said by others in the sphere of abstract art, apart from Lewis; before Lewis and the American poet, Ezra Pound, began sticking their Vorticist labels upon our productions. These 1914 numbers of The New Age help one to visualise the scene as it was in reality at that time, composed not with the figure of a single 'Leader' in the person of Wyndham Lewis surrounded by a herd of Adherents, Disciples and Professed Followers, influence-drenched and impact-dazed, but on the contrary a criss-cross of opposed interests between rivals eager to establish themselves and their own particular brand of abstract art.

We have T. E. Hulme and the Anglo-Jewish Cubists together with Nevinson's Italian Futurists against the Francophile Roger Fry. Wyndham Lewis with the Americans attacking all and sundry; whilst into this mêlée, adding to the general confusion, charges Walter Sickert with his cockneys. 'No Disciples! No Adherents!' was the battle-cry in those days.

And now, after an interval of forty-two years, we have Sir John – in the hope that all is forgotten under the rubble of two world wars – exhibiting at the Tate a masterpiece that he claims to be a genuine picture of the 1913–1914 scene. Instead of 'Lewis and Vorticism', I suggest the title should have been 'A Deity of Vorticism with a group of adoring Neophytes'. For the benefit of conscientious historians of art, I would like to add that copies of The New Age dealing with the English Cubists can be inspected at the Newspaper Section of the British Museum Library at Colindale, N.W. 9.

This examination of the events during 1913–14 has clearly shown that Vorticism did not precede the germination of English Cubism, but was a kind of exotic growth nurtured later by certain cultivators in the hope that it would overgrow and supplant the earlier flowering Cubism. Realising that the art critics and the Director of the Tate are specialists in the subject of art history, whose statements are fully authenticated before appearing in print, it seemed possible there was some more recent record to support their claims, of which I had no knowledge. So let's research a little more. The date 1949 should help, for it was in May of that year that Lewis had an important retrospective exhibition of his paintings at the Redfern Gallery. The catalogue, although not so magnificent as the Tate's, is impressive enough, with six large reproductions and two introductions – one by Lewis, the other by Michael Ayrton. But it is the contrast, not the similarity, of 1949 to 1956 that strikes one so forcibly. Lewis is not surrounded here by 'Contemporaries who have felt his immediate impact', or by 'Professed Followers' of any sort (save perhaps Michael Ayrton), but by something quite opposite. It is SILENCE – an awful overwhelming silence that envelops us. There is so much of it that Ayrton suspects a conspiracy; whilst Lewis informs us that this barrier of silence has been piling up around him since 1913.

What, then, is the explanation for the change from the silence and emptiness of the landscape in 1949 to the crowds of jostling 'Adherents and Followers' who fill the scene in 1956? Well, we owe this transformation to the genius of one man, Sir John Maurice Knewstubb Rothenstein, C.B.E., PH.D., M.A., F.M.A., Knight Commander of the Aztec Eagle, whose Brain-Wave, 'His immediate impact upon his contemporaries', has enabled the 'Leader' to break through this long-resisting 'Sound-Less-Barrier' to public notice at last.

This 1956 slogan devised at the Tate – 'Lewis's impact upon his Contemporaries' – reminds me of the 'Impacts' the contemporaries of 1914 really inflicted upon each other. Take the occasion of the opening of the first London Group exhibition at the Goupil Salon. To celebrate this event, Bomberg, Lewis and myself had arranged that on the evening of Private View Day we would have dinner together at a Jewish restaurant in Whitechapel, opposite the Pavilion Theatre, and go to a Yiddish play afterwards. There was to be Palestinian wine, Wiener Schnitzel, Russian cigarettes and Russian lemon tea, and to make our evening's enjoyment complete, Bomberg had promised to bring a couple of black-haired, dark-eyed East End Rebeccas. On the previous day, at the hanging of the pictures, Bomberg had secured himself an excellent central position for his painting and was feeling very happy indeed about it.

But on this day of the Private View he made a discovery that left him speechless: astounded, he saw hanging in this much-coveted spot on the wall a painting by Wyndham Lewis, and his own rehung in a less prominent position. In a fury, he laid plans for a showdown with Lewis at our dinner party that evening. Bomberg, although pugnacious and spirited, is but half the stature of Lewis; I should say rather in the proportion that Sir John stands to Douglas Cooper. So instead of the beautiful brunettes Bomberg brought to our rendezvous his boxer brother, 'American Mowie'.

After the soup, Bomberg, raising his voice to a loud strident pitch, said suddenly to Lewis, 'Say, Wyndham, what do you mean by taking my painting down and sticking your own up in its place?'

If 'American Mowie' was expecting to be able to display his pugilistic talents he was disappointed, for although at first Lewis made an attempt to protest, he stopped, rose suddenly from his seat, and throwing his theatre ticket upon the table abruptly left the restaurant in haste to escape from the hostile atmosphere of the East End back to the friendly gaiety of Soho.

Following the exhibition at the Tate of Wyndham Lewis and Vorticism, I sent to David Bomberg, who now lives near Malaga in Spain, a package with this note:

August 1956

Dear Bomberg,

If you can spare a moment and take your attention off the Rock of Gibraltar, I am sure you will be interested to know what Sir John Rothenstein is trying to do with the rock of your reputation as one of the original Cubist artists in England.

I enclose the Tate Catalogue and the Arts Council Catalogue, together with two pamphlets that I have produced in reply. The exhibition is at present in Manchester.

Yours, etc.

To this message I received no answer. Evidently the old lion was not to be enticed from his lair in the sun.

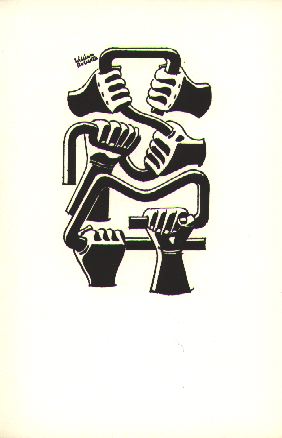

Endpiece, 'The Wire-pullers', and back cover of Vortex Pamphlet No. 3

Home page | Chronology | Bibliography | Collections | Exhibitions

News | Gallery | Auction results | The artist’s house | Contact

List of works illustrated on the site

Catalogue raisonné:

chronological | alphabetical