AN ENGLISH CUBIST

DAVID CLEALL:

William Roberts, Modernism and Dance

Illustration © The Estate of John David Roberts. Text © David Cleall, from the January 2015 William Roberts Society Newsletter.

The Toe Dancer, 1914

Ink and gouache, 72 cm x 54 cm

The inclusion of William Roberts's extraordinary drawing The Toe Dancer 1914 in the exhibition 'Gaudier-Brzeska: New Rhythms. Art, Dance and Movement in London 1911–1915' at Kettle's YardGallery, Cambridge, in March–June 2015 serves as a reminder that, like many of his fellow modernists, Roberts was not immune from the excitement about dance that swept the capital in the years before the First World War.

'Wild, bizarre, naive, barbaric, entrancing, beautiful', as Peter Brooker described them in Bohemia in London, his book on the social scene of early modernism [1], Diaghilev's Ballets Russes came to London for the first time in 1911 and returned on several occasions before the war. This period also saw Roger Fry's 'Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition', which in 1912 brought to the Grafton Galleries Henri Matisse's Dance I. The Times critic of 1912 felt that '[Matisse] is not interested in his dancers as women. He is interested in the rhythm which they make together.' [2]

It is quite possible that Roberts saw the Ballets Russes in 1913, during his last year at the Slade. Ezra Pound's poem 'Les Millwins' describes a 'turbulent and undisciplined host of art students' from the Slade attending a performance by the Ballets Russes in London in March of that year. [3] Although the poem specifically mentions a performance of Michel Fokine's ballet Cléopâtre, it is most likely that the students' excitement related to the other work on the bill that evening – L'Après-midi d'un faune, with Vaslav Nijinsky, who choreographed the piece, in the principal role. Both ballets were designed by Léon Bakst.

Roberts's best friend from the Slade, David Bomberg, was friendly with the Russian Ballet dancer Maria Wajda, and had other dancer friends from the East End. He took inspiration from the Ballets Russes for an artist's book of six richly coloured lithographs, Russian Ballet, published in 1919 but based on pre-war sketches.

After leaving the Slade, Bomberg and Roberts were for a brief period both members of an artists' commune in Primrose Hill, at the house of the Scottish solicitor-turned-hunger-marcher Stewart Gray. It was here that Bomberg met Alice Mayes, a dancer with Kosslov's Ballet Company, who had been invited to the house to demonstrate 'Russian Dance Steps'. Bomberg and Mayes would marry in 1916. And it was at a party at this house in Ormonde Terrace that Roberts was inspired to create his extraordinary The Toe Dancer.

Unlike Bomberg's, Roberts's dance subjects take their inspiration from popular dance forms. The turkey trot, the bunny hug and 'shaking the shimmy' had a sensuality and a raw sexuality that shocked the middle-classes as much as Fry's post-Impressionists had rattled the popular press. In 1912 the Cave of the Golden Calf, a basement nightclub off Regent Street, had been opened by Madame Strindberg, a former wife of the Swedish playwright – 'a small plump pale-complexioned brunette, with a forceful manner', according to Roberts. [4] With decorations by Wyndham Lewis, Spencer Gore and Eric Gill, this exemplified the exciting contemporary collision between popular dance, ragtime jazz and the visual arts. The description 'ragtime' seems to have embraced a wide range of musical forms beyond jazz, including tango, apache and veil dances. Isadora Duncan, who was associated with this scene, was renowned for the sensuality of her dance performances, and her daring, flimsy costumes probably inspired Nina Hammett, artist, model and 'Queen of Bohemia', who was not averse to dancing naked.

This atmosphere seems to have been paralled somewhat in the Ormonde Terrace party of The Toe Dancer. The focus of the picture is an eccentric dance performance from Stewart Gray's wife, who is performing semi-naked and appears to be morphing into Vorticist abstraction, as does a male dancer in the background. The Toe Dancer would be exhibited by Roberts in the second exhibition of the London Group, in March 1915.

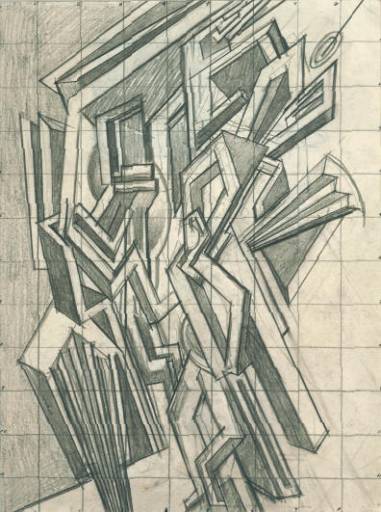

The two highly abstract studies for Two-step from 1915 also in the Gaudier-Brzeska exhibition at Kettle's Yard show Roberts at his most Vorticist. The two-step, which pre-dated ragtime, was a more lively form of the waltz, but, while popular with a younger generation, it did not elicit the wild abandon associated with the Golden Calf. However, from these studies, Roberts's painting would appear to be uncompromising. Two-step was exhibited in the Doré Gallery' 'Vorticist Exhibition' in June 1915 – a show that included Gaudier-Brzeska's sculpture Dancer, which provides one of the focuses of the Kettle's Yard show. Unfortunately the present whereabouts of Roberts's painting is unknown.

Two-step I, 1915

Pencil, 30 cm x 23 cm

To get an idea of a fully developed Roberts dance-related work of the time we can look at The Dancers. In April 1914 a study for this work was reproduced in the magazine The New Age, where the critic T. E. Hulme dissuaded viewers from trying to unpick the details of the work too assiduously: 'This drawing contains four figures. I could point out the position of these figures in more detail, but I think such detailed indication misleading . . . The interest of the drawing itself depends on the forms it contains. The fact that such forms were suggested by human figures is of no importance.' [5] This comment, which is surprisingly similar to the Times critic's account of Matisse's Dance I quoted above, would later be contested by Roberts. [6]

The Dancers – study, 1913–14

Tempera on board, 51.4 cm x 51.4 cm (?)

Wyndham Lewis published a reproduction of the final version of The Dancers in the first issue of Blast magazine, in June 1914, and while the quality of the reproduction is poor it does provide us with a record of a fully realised Roberts Vorticist oil painting. Richard Cork in 1974 commented that it was 'an incredibly precocious achievement for a young artist of 18 years of age'. [7] This painting was probably the picture exhibited as The Dance in the Whitechapel Gallery's exhibition 'Twentieth Century Art – A Review of Modern Movements' in the summer of 1914, after which no definite record of it exists.

After Roberts had been withdrawn from military service in 1918 and completed two war-artist commissions, he turned again to dance as a suitable modernist subject. Following a lively drawing Dance with Tambourines, a pencil study for The Dancers does not prepare us for the impact of the finished work – a large panel painted as part of a triptych to be hung outside the upstairs 'Vorticist Saloon' (decorated by Wyndham Lewis) of the Hôtel de la Tour Eiffel in Fitzrovia. While the scale, the graphic qualities and the bold colour contrasts might be expected to communicate a vibrancy appropriate to dance, there is something mournful and disturbing in the highly stylised couples shuffling rather claustrophobically around the dance floor.

The Dancers, 1919

Oil on canvas, 152 cm x 116.5 cm

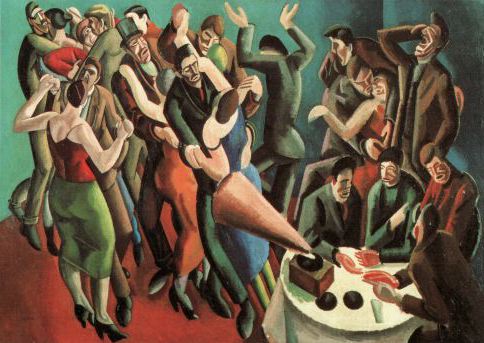

If a legacy of Roberts's war experiences can be detected in this panel, a further dance subject, from 1921, is a much more upbeat rendering of a similar scene. The Dance Club (or The Jazz Party), owned by Leeds City Art Gallery since 1928, is a lively, angular highly coloured work that places at its centre an exuberant individual who has broken away from the dancing couples and with hands raised above his head has surrendered to the music. The Dance Club is a popular, often-reproduced work, as it so much stands for the twenties as the 'Jazz Age'. In 1985 Richard Cork interviewed Sarah Roberts, who said that her husband liked to dance and 'was a good dancer'. [8] While I can't imagine him taking centre stage in wild abandon, I would like to think that he and Sarah had themselves enjoyed a two-step at a modest venue such as this club.

The Dance Club, 1921

Oil on canvas, 76 cm x 106.6 cm

NOTES

[1] Peter Brooker, Bohemia in London: The Social Scene of Early Modernism (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), p. 81

[2] 'A Post-Impressionist Exhibition', The Times, 4 October 1912.

[3] Ezra Pound, 'Lustra II', Poetry 3, 2 (November 1913), p. 57.

[4] William Roberts, 'The "Twenties"', in Five Posthumous Essays and Other Writings (Valencia, 1990), p. 137.

[5] T. E. Hulme, 'Study by W. Roberts', New Age 14, 24 (16 April 1914), p. 753.

[6] In William Roberts, Some Early Abstract and Cubist Work 1913–1920 (London, 1957).

[7] Richard Cork, Vorticism and Its Allies (Arts Council, 1974), p. 40.

[8] Richard Cork, Art Beyond the Gallery in Early 20th Century England (London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985), p. 244.

Home page | Chronology | Bibliography | Collections | Exhibitions

News | Gallery | Auction results | The artist’s house | Contact

List of works illustrated on the site

Catalogue raisonné:

chronological | alphabetical