Outside the pubs fights were frequent, and as the blood and beer mingled, the children

danced to the tunes of a wheezy barrel organ. Toffee apples were a popular delicacy,

and the old woman who sold them, when compelled to answer nature's call, but afraid

to leave her toffee apples unguarded, would straddle her legs, well knowing that under

that long heavy pleated skirt, there was no risk of wet underclothes.

In Summer, London Fields offered opportunities for games and sport; there was besides

a chance for the boys to earn a few pennies collecting the stray tennis balls that

came hurtling across the courts. But in Winter the favourite assembly place for the

lads of the neighbourhood was a small line of shops known as 'the Top', where they kept

warm on cold nights, standing on the iron grid over Mr. Tidy's basement bakehouse.

At the age of three years, I was sent to Gayhurst Road School, which was only a couple

of streets away from the house my parents lived in. There is little worth recording

of my early school years, except perhaps the ambitious attempt of one of our masters

to teach the class French; however it could hardly have been part of our normal instruction,

and he soon gave up the idea after we had learned to repeat the sentence: 'Ouvrez

la porte, s'il vous plaît.'

It was about my twelfth year that my interest in drawing began to attract the notice

of my teachers, with the result that I was permitted to omit some of the regular

lessons and devote more time to the subject that interested me most. Further, every

Friday a visiting art-mistress came to the school, bringing flowers, which we had to draw.

These lessons took place in a room equipped with all the paraphernalia: cubes, cylinders

and plaster casts of objects that could be arranged to form still-lifes, in fact

a genuine general drawing or antique room. Here the boys attended in the morning, and

the girls in the afternoon. On other days, when the Friday class was not in session,

I stood at an easel in a corner of my regular classroom and painted in water-colour,

either a large-sized copy of a Venice scene by Turner or else some still-life arrangement

of my own.

About this period I did a full-length figure as a poster to advertise the school's

performance of Shakespeare's 'As You Like It'. The design, a single figure of an

Elizabethan forester, was placed at one corner of the stage. When the play was over,

there was a call from the audience (composed mostly of parents) for the cast and the artist

to take a bow. Standing in the wings, I was reluctant to show myself, when a sudden

push from behind sent me staggering across the stage, to the accompaniment of the

applause and laughter of the audience; with an awkward bow, I made a quick exit from the

platform.

To further my Art education, I was taken one wintry Saturday afternoon to the Tate

Gallery by the Friday art-class mistress, whose name at this late date I cannot remember.

In the Gallery, she drew my attention to a large painting of a river scene with barges at sundown; its title was 'Toil, Glitter, Crime and Wealth', and the artist's

name was I think Maurice Greiffenhagen. As we stood awhile gazing at this picture

with its foreboding title, the grey afternoon seemed to become even more overcast.

However, our visit to the Tate ended more cheerfully with tea at an A.B.C. opposite Westminster

Bridge.

About this time the headmaster at Gayhurst Road School, deciding that one half-day

a week was not enough art instruction for me, arranged that I should attend at the

nearby Queen's Road school, where they had art-classes two days a week, and two visiting

art-mistresses. One of these, Miss Mathews, helped me still further in my desire to

become an artist by introducing me to her fiancé William Robins, a teacher at the

old St. Martin's School of Art.

A final gesture during my last summer at Gayhurst Road was the making of a large drawing

of the school building. So, at about six o'clock in the morning – to avoid publicity – my father carrying his home-made easel and I an Imperial size drawing board, we clambered

over the railings and set up our equipment in London Fields facing the school. However,

the drawing was a failure, chiefly because I attempted to draw the building brick by brick.

I had now reached the school-leaving age of 14 years, and must look around for a job.

With the addresses of several firms, producers of commercial art, and carrying a

large portfolio of drawings done at home and at school, my first day's target was

to have been W. H. Smith and Sons, the magazine distributors; but I called on the wrong Smith,

a shop off Kingsway which dealt in old prints and engravings, and they had no use

for my work. The next day I paid a visit to Liberty's, who also turned me down. Although beginning to tire of these daily journeys around the West End, I decided to try

one more address. This was Sir Joseph Causton's, a firm of law stationers, producers

of posters and other kinds of commercial art. Their offices were in Eastcheap, near

the Billingsgate fish market.

Here I was more successful, for Causton's took me on a seven-year apprenticeship;

at the same time Robins arranged for me to attend his evening classes at St. Martin's,

after my day's work at Causton's, which began at 8 a.m. and finished at 6 p.m. Eastcheap in the early morning presented an animated scene, with the long lines of horse-drawn

carts and vans of the fishmongers parked by the kerbs, awaiting their consignments

of haddocks, herrings and codfish; while the Billingsgate porters, wearing their

queer hats for carrying the heavy crates of fish on their heads, hurried around shouting

the names of their customers. Meanwhile down by the Thames side where the barges

were unloading, was a scene, if not of crime, certainly of toil, glitter and wealth.

Sir Joseph Causton's firm employed some twelve commercial artists, who specialised

in various types of work; some did only large-lettered advertisements, others were

expert in small lettering suitable for showcards. Except for the chief artist, Mr

Wise, who had a small room to himself, the others worked at desks arranged around the large

sky-lighted top studio. The chief artist, when not busy with the air brush, an instrument

for spraying paint, was frequently in consultation with Sir Joseph, whose office

was on the ground floor. A room below the main studios was shared by two men: Johnson,

a grey-bearded man, who did large-size poster lettering; and a younger one, an expert

at small-scale show-card wording.

On the top sky-lighted floor were quartered the main group of designers. First came

Harry Stubbs, a fair-haired, frizzy-moustached Yorkshireman. I was never able to

discover what Harry's work as a draughtsman was like. His continual patter, which

amused the others in the studio, had the quality of a Yorkshire comedian; his satirical wit

was directed mainly against another member of the studio, George Ball. In these satires

Harry would pretend to be a very aristocratic, amorous lady in love with George.

After George's arrival had been announced her ladyship would say 'Oooh, come in, George,

take your trousers off, George.' At this point there was laughter from the other

artists, including George, who seemed to enjoy the fun as much as the rest of the

studio. Harry was very resourceful at inventing these amorous adventures of George's, which

surpassed those of Casanova and Don Juan combined, and was most inspired after his

mid-morning mug of hot milk and A.B.C. lunch cake.

From the artistic point of view the star of the studio was a tall middle-aged Scotsman,

David Wilson, well-known as a freelance illustrator and cartoonist. He seemed much

concerned with his family troubles. Another artist fond of joking was a tall athletic young man named Harris. He specialised in large posters of over-lifesized footballers

in action painted in a flourishing style reminiscent of Sargent. I was a victim of

one of his pranks; complaining that he had a headache, he asked me to get him a 'Grouse Powder' from the chemist; but the only thing I got from the druggist was a laugh.

Harris shared a room with two other artists; one a marine artist named Weekes, who

produced display cards of ocean-going liners for the big shipping companies. I remember

nothing of the third man except that he was fond of swimming. To end the list of Causton's

chief designers there was a man with one leg who used a crutch and lived in Dulwich,

and another known as Gossy who seemed to be a kind of odd-moments fun organiser.

Besides the humour of Harry Stubbs, the artists found amusement in other ways. Thus,

when the opportunity presented, they played a kind of indoor golf, using yardsticks

as golf clubs to knock a little ball of tightly-wrapped paper into rings chalked

on the floor. The game started whenever the head artist went downstairs to consult with

Sir Joseph upon matters of business, and would end abruptly when the pounding footsteps

of the returning chief could be heard charging up the stairs three at a time (he

was a tall athletic man) causing the players to scamper back to their desks.

Sometimes freelance artists would call at Causton's trying to dispose of their work.

On one of these occasions Gossy arrived breathless from the ground floor with the

news that Mrs. Barribol was downstairs trying to sell to the Firm some of her husband's

work. Barribol was a well-known commercial artist who painted only dark-eyed black-haired

types of feminine beauty, using always the same model, his wife. These alluring portraits

eventually became known as the Barribol girl. It would seem from Gossy's announcement that the Barribol girl could also at times become a saleslady.

One of my jobs in the studio was mixing paint when required. This was done with a

large palette knife on an old litho stone. I also had to replenish the water buckets

from which those artists using Gouache drew their supply of water. These pails of

water could also be a source of amusement, as we realised when Harry Stubbs and Gossy attempted

with considerable splash, to put George Ball headfirst into one of them. In spite

of these distractions I was able to practise a little lettering, or copy a showcard.

One of these I still remember; it was an advertisement for typewriters. It showed

a figure of Father Time, complete with scythe and hour-glass, standing behind a typewriter;

the card bore the caption: 'Time flies; so does the Bar-Lock in the hands of the

operator.'

When the workday ended at six o'clock, I walked through Cheapside and Holborn to St.

Martin's School of Art in Endell Street, near Drury Lane. Here I spent the evening

until nine o'clock, when the class ended, drawing from plaster casts of Greek or

Renaissance sculpture. However, on reaching home at ten o'clock my day was not yet ended;

there was still work to be done on a portrait of the Gayhurst Road School headmaster,

which when finished was to be presented to him. This, like the drawing of the school,

was an idea of my father's.

So after supper the painting was brought out and placed on its easel, and in a room

dimly lighted by a small oil lamp that hung from the ceiling – we had no gas or electricity – I endeavoured, half-asleep, to carry on with the painting. As a model for the portrait

I used a photograph, showing some thirty of my classmates, with the headmaster sitting

in the centre of the group; his face had to be enlarged from half an inch to life size, to fill the two foot square rough, unprepared piece of sackcloth. With its

dark background and concentrated light on the face it looked slightly Rembrandtesque.

However it remained unfinished, and Mr Walker never received his portrait. Finally

painting in the dark, half-awake, became too much for me.

Meanwhile, at St. Martin's, I continued my evening classes. Another student, working

for his Art Master's Certificate, was drawing the Venus de Milo by a method known

as stippling, and from time to time he would study the figure through a pair of binoculars; these would enable him to record every crack and blemish in the plaster. Whether

he got his Art Master's Certificate I cannot say, as I left St. Martin's before his

masterpiece of stippling was finished. At one of the school sketch club shows I won

a prize of half-a-crown, which I received from the treasurer, a grey-bearded Scotsman

named McPhee. At another of our sketch club meetings, Harold Speed came and criticised

the exhibits. He was well known for his contributions to the Royal Academy, and his

portrait of Edward the Seventh, shown at the Paris Salon.

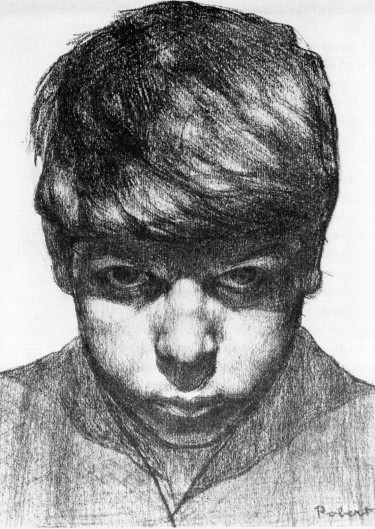

One evening while drawing a cast of the head of Michael Angelo's 'David,' Robins came

to me and said 'Take a look in the Life Room, there is a male model posing there

with a marvellous figure.' I did not know, as I took a look, that the model was David

Bomberg, or that in a year's time I would be drawing him as he posed in the Life Room

at the Slade. Besides his art-school posing, Bomberg also stood for the statue of

Lycidas that Havard Thomas made, when he and his family lived in one of Sir Cyril Butler's cottages in Bourton in Berkshire. This bronze figure of David (Lycidas) Bomberg

now stands with arms upraised, in the entrance hall of the Tate Gallery.

The drawings I did at the St. Martin's evening classes won me a scholarship to the

Slade. This event brought me release – after one year – from the seven years apprenticeship contracted with Causton's. On my last day with

the firm I went to each of the artists in turn to take my leave. I got a characteristic

goodbye from Harry Stubbs, when he said he hoped I would get to the top of the tree, but warned me to be careful not to fall and break my bloody neck.

For St. Martin's it was also goodbye; I ceased to attend the old school's evening

classes once my Slade days had begun.

When I joined the Slade in 1911, the teaching staff consisted of Professor Fred Brown,

Henry Tonks, Walter Russell, Wilson Steer and Derwent Lees. With the exception of

Augustus John and Wyndham Lewis, who had already left, among the students still working there at that time were some who were later to become important as artists, such

as Stanley Spencer, Nevinson, Allinson and Wadsworth. Others less celebrated included

a retired Indian Army doctor and a corpulent ex-business man, nick-named by Nevinson

'Have a Smoke,' from his habit of offering cigarettes around. Another target for Nevinson's

gibes was an old grey-haired Italian model, who as a young man had posed for Millais' painting, entitled 'Speak, Speak!' He

was very proud of this, and would tell the students 'Me Speak, Speak' until with

Nevinson's help he became known in the Life Class as 'Me Speak Speak.' Models who

posed in the art schools at that period were mostly Italian, with names like Marc Antonio or

Mancini; in the summer when the art schools were closed they sold ice-cream.

After a short spell drawing from the Antique, I moved down to the Life Room. Toward

the end of my first morning there, the female model fainted and collapsed on the

throne; the army doctor promptly took off his jacket, covered her prostrate naked

form with it, then strolled off unconcernedly to lunch.

About 1912 there was an influx of Jewish students at the Slade, sponsored by the Jewish

Aid Society. Mark Gertler had been the forerunner of this group, that included Meninsky,

Rosenberg, Bomberg – no longer a model – Kramer and Goldstein; apart from these, there were several independents, like Solomon

and Lowinsky, rich enough to pay their own tuition fees.

It was a surprise one morning to see Bomberg walk into the Life Room, a drawing board

under his arm, bestride a donkey and start to draw. When Nevinson left, Bomberg became

the official wit of the Life Class, but with a more aggressive style. This sometimes led to a 'punch-up'. A young Frenchman named Detry, a newcomer to the Life Class,

liked to boast about his strength, saying 'I am very strong here and here,' indicating

at the same time different parts of his anatomy. Thus when the class was quiet, except for the scratching of charcoal on Michelet paper, Bomberg would suddenly shout 'I

am very strong here and here!' This he repeated from time to time until the exasperated

Frenchman could bear it no longer. Leaving his donkey he went over to Bomberg and

a fight began. During the scuffle Detry received a punch that put him on the floor,

but scrambling up at once he seized a drawing board and hurled it at Bomberg, who

promptly jumped clear in time. Quiet was restored with the arrival of Tonks to find

out the cause of the disturbance.

There was one other, but a more friendly contest, in which Bomberg took part; this

was a wrestling match when the class was ended – with the Italian model. After rolling about a good deal on the dusty floor of the

Life Room, locked together in a tight embrace, Bomberg finally managed to come out

on top. However, this mini-Hercules had his more gentle moods; when for instance

he got the poet and fellow student Isaac Rosenberg to write him a verse or two, to win the

favour of a certain Jewish girl student. This was confided to me by Rosenberg, who

was amused at the thought of Bomberg taking part in this kind of Cyrano de Bergerac

scene.

Besides these student diversions, however, there was a more serious side to our studies.

Tonks was anxious to encourage our interest in mural painting, and to this end had

obtained permission to decorate the walls of a girls' club in Lillie Road, Fulham.

About half a dozen students took part in the scheme. The compositions were done in

egg tempera, on paper stretched on the walls. My contribution was a panel showing

carpenters at work. The only other design I can recall was one by Dora Carrington

of blacksmiths hammering on an anvil, rather reminiscent, I thought, of Puvis de Chavanne's

painting of a similar subject.

When the murals were finished, Tonks gave a dinner party at his house in the Vale

at Chelsea, to the students who had carried out the decorations. A number of other

guests were also present, among them George Moore. Dora Carrington, with some others

of the team of decorators, tried to persuade George Moore to come and see the panels. But

relaxed comfortably in his chair, his hands folded in his lap, he declined their

invitation, saying that no painting worth looking at had been done since Degas.

In the summer of 1911 three Slade students were invited to stay a month, alternately,

at the farm of Frederick Harrison, near Wellington, in Somerset. Gertler, the first

to go, chose July; when his month ended, Spencer followed, in August; while I, the

last on the list, had September. A country mansion would well describe Harrison's place,

with its stables for hunters and a numerous domestic staff. Harrison had his brother

and two nephews staying with him. The nephews were military cadets from Woolwich,

who amused themselves, with the help of a mule, dredging a nearby ditch. To get to the

room where I lodged, I had to pass the stables; one of my equine neighbours, his

head above the stable door, always watched me with interest whenever I passed by.

At the end of September I returned to London bringing with me a large hamper packed

with apples, and some rabbits, these last the result of a morning's shoot. In the

summer vacations of the following year, I received another invitation to spend a

few weeks in the country; this time from Sir Cyril Butler – a friend of Prof. Tonks and a patron of the group of artists, members of the New

English Art Club. Bourton House, where Butler lived, was a large country mansion

near Shrivenham in Berkshire, set in extensive parkland. Within the house there was

evidence of wealth and well-being; a nursery and a French governess for the two young daughters;

visitors' shoes left at night outside their room doors were found the next morning

brightly polished; and for those guests who suffered from 'night-starvation' there

were tins of biscuits on their bedside tables.

I had been only a few days at Bourton House, when a large canvas some twelve feet

square arrived; on it was faintly scumbled in pale blue the beginnings of what appeared

to be a seated woman flanked by two children. This canvas was placed in a large room,

with spacious windows that overlooked the park; the interior walls were hung with

paintings by Wilson Steer and other New English Art Club members. A week later whilst

we were having tea, a little man who spoke with a shrill squeaky voice was shown

in by one of the maids. This was the celebrated portrait painter Ambrose McEvoy, come to

finish his painting of the Butler family. However I did not stay long enough at Bourton

to see its completion. I remember a meeting in the library shortly before my departure, when the family gathered to pass judgement on some small paintings Sir Cyril had

bought in London. After studying the pictures awhile in silence, his daughters expressed

their opinion with the remark, 'Daddy, you've been done this time.'

Following on my stay at Bourton, Sir Cyril commissioned me to do six drawings of London

markets at two guineas each. But except for two markets, Billingsgate and Leadenhall, the drawings were never carried out. Several years after this, about 1919, I was

living in an attic at 32 Percy Street, Tottenham Court Road, and being very hard

up I wrote to Sir Cyril, hoping he might feel interested in buying a drawing or perhaps

complete that set of London markets. He did not reply; instead, he called one evening;

the visit was brief. After asking me what artists I associated with, and who my friends

were, without mentioning the market drawings he departed, leaving me no better off

than before.

Long after this Percy Street meeting had been forgotten, I was on a cycling tour in

Berkshire, and found myself in the vicinity of Bourton House. Remembering the time

when as a student I had once stayed there, I wandered into the nearby village churchyard. Among the old gravestones, two small more recent ones attracted my attention; on

each separate stone was carved the name of a Butler girl. What, I wondered, could

have brought them to these early graves?

The summer term of 1913 was my last at the Slade; when it was ended I took a short

holiday in Italy. On my return to London I was lent a room belonging to a friend,

an actor who had gone on a provincial tour with a theatrical company. In this little

room in the old Cumberland Hay Market I painted my first 'Abstract' pictures. There were

no Arts Council's or Student's Grants in 1913, and my 'Abstracts' had no monetary

value at that date either; nevertheless I had to make a living. So with a letter

of recommendation from Laurence Binyon, of the British Museum Print Room, I called on Roger

Fry at his Omega Workshop in Fitzroy Square, where I got employment painting designs

on paper knives, lampshades, tabletops and silk scarves, three mornings a week at

a salary of a half-sovereign a visit, that a little sandy-bearded Scottish secretary took

from a small cash box. With no rent to pay, and a salary of thirty shillings, in

those days that was independence.

When I started at the Omega, three of Fry's assistants, Lewis, Etchells and Wadsworth,

had already left. Later on, Lewis, hearing that I was working with Fry, contacted

me; this meeting brought about my departure from the Omega. From the Autumn of 1914

till the end of 1915 except for a few weeks working in a munitions factory, I continued

my Cubistic painting, associating with the artists who had once been part of Roger

Fry's Omega workshop group. However in March 1916 an end was put to these activities,

by my entry into the Royal Field Artillery. A few months before the termination of this

first world war, I became an 'Official Artist' to the Canadian War Records Office,

and also to the English Ministry of Information.

In 1920 Colin Gill, who had been a fellow-student at the Slade, sent me a note saying

'Colonel Lawrence is seeking artists to make portrait drawings for a book he is producing;

get in touch with him.' I wrote to Lawrence and as a result I contributed several portrait drawings to 'Seven Pillars of Wisdom,' besides a painting of Lawrence

in his Royal Air Force uniform. He sat for this portrait in a room I was using at

Coleherne Terrace, Earl's Court. Sometimes if I was late for our meeting I found

him sitting on the dark stairs that led to my temporary studio. He lent me during several Summers

his small woodman's cottage at Clouds Hill in Dorset.

About 1935 I became a member of 'The London Artists' Association.' This was a scheme

sponsored by Maynard Keynes and Samuel Courtauld to assist young little-known artists

of merit, – also some not so young, and better known – in the sale of their work. This Association continued to function till in 1939 the

coming of the second world war brought it to an end. In the years immediately following

the finish of this second conflict I began to exhibit at the Royal Academy, and in

1948 I was nominated for election as an associate. Ten years passed, till on the 6th

of May 1958 I received a letter from the Secretary of the Royal Academy informing

me that I had been elected an Associate of the Academy. (This had been achieved by

the President's casting vote.)

September 1977

Home page | Chronology | Bibliography | Collections | Exhibitions

News | Gallery | Auction results | The

artist’s house | Contact

List of works illustrated on the site

Catalogue raisonné:

chronological | alphabetical

|