AN ENGLISH CUBIST

WILLIAM ROBERTS:

Cometism and Vorticism:

A Tate Gallery Catalogue Revised

[Vortex Pamphlet No. 2]For the context in which this pamphlet was published, see John David Roberts, 'A Brief Discussion of the Vortex Pamphlets'. The ellipses in the text are Roberts's own. Text and illustrations © The Estate of John David Roberts.

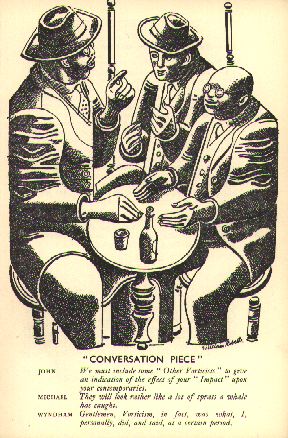

JOHN We must include some 'Other Vorticists' to give

an indication of the effect of your 'Impact' upon

your contemporaries.

MICHAEL They will look rather like a lot of sprats a whale

has caught.

WYNDHAM Gentlemen, Vorticism, in fact, was what, I,

personally, did, and said, at a certain period.

Cover and frontispiece for Vortex Pamphlet No. 2

'LEWIS THE LEADER' LEGEND

or

How Group Leaders are made at the Tate Gallery

This Pamphlet is offered as a supplement to the Tate Gallery Catalogue of the retrospective exhibition of Wyndham Lewis's paintings, with the object of correcting the impression it gives that in 1914 Lewis was a brilliant leader of the group of abstract artists active in London at that time. Or that his ideas upon painting were as revolutionary as his Introduction would have one believe.

The authors of this pink publication have intended it to be more than a catalogue. It is a veritable Manifesto, a little Blast, worthy progeny indeed of that corpulent pink old Blast of 1914.

This is also an attempt by the Art Soothsayers on the banks of the Thames to raise their Protégé out of the ancient waters of the Vortex, now become sluggish, and send him rejuvenated, careering comet-like, into the luminous stratosphere of the future for the benefit of the yet unborn generations of Courtauld Graduates.

Yes, this Catalogue certainly has a head and a tail. The dazzling head consists of two introductions, a mass of biographical data, together with a gay cluster of reproductions; whereas, the list of artists' names at the tail-end resembles a scattered trail of burnt-out sparks.

Lewis in his introduction stresses the originality of the ideas he held about painting around 1914, but because the Vorticist slogan signifies for him his life's work as an artist, some of his more recent notions have got pushed back into this early period. To strengthen no doubt the claim that he was an innovator in those days.

Here are some extracts from his Introduction. 'It was my ultimate aim to exclude from painting the every-day visual real altogether.' Revolutionary? But the Cubists had been working at just that in Paris for a number of years already prior to 1914. As, too, the Futurists in Italy.

Also . . . 'The idea was to build up a visual language as abstract as music'. Is this revolution? Kandinsky in 1912, in his book On the Spiritual in Art and a whole series of paintings, was already developing this theory.

Again . . . 'I considered the world of machinery as real to us, or more so, as nature forms, such as trees, leaves and so forth, and machine forms had an equal right to exist in our canvases.'

This 1914 blossom fades somewhat on reading Marinetti's declaration in his 1912 Manifesto to the Futurist exhibition at the Sackville Gallery in London . . . 'We declare that the world's splendour has been enriched by a new beauty – the beauty of speed. A racing motor-car, its frame adorned with great pipes like snakes with explosive breath; a roaring motor-car which looks as though running on shrapnel, is more beautiful than the "Victory of Samothrace"'.

These ideas which were part of the Art atmosphere of the period, which we all breathed, have become now, in 1956, the amazingly original and revolutionary ideas of P. Wyndham Lewis, to be 'accepted'. Accepted by colleagues like Wadsworth. Why should this be so? Had not Wadsworth the same opportunity to acquaint himself with the works of Picasso, Braque and Kandinsky, as Lewis? Later, these 'accepted' ideas of the 'Leader' crystalise into a 'teaching' which the master afterwards 'repudiates' just as later the 'Colleagues' are repudiated in the famous phrase . . . 'Vorticism, in fact, was what I, personally, did and said at a certain period.'

To be a teacher one must have pupils and pupils are found in schools, hence the need for this Tail-piece or School of Wyndham Lewis.

It is interesting to see how thoroughly the Gallery Fabulists have got to work on Lewis's behalf in their fabulous catalogue. Although Wyndham Lewis, with a flourish of the pen, has got rid of his former colleagues and now stands unique upon his Vortex pedestal, nevertheless part of the Official Plan is to have the 'Minor Artists' grouped at a respectful distance in the rear.

Down at Millbank they believe in legends. Sir John Rothenstein has lent official support to the 'Leader' legend in his contribution to the Catalogue when he writes: 'The Trustees of the Tate Gallery have decided to give the public an opportunity of forming a fuller estimate than has been possible hitherto of the painting and drawings of Lewis, . . . and AN INDICATION OF THE EFFECT OF HIS IMMEDIATE IMPACT UPON HIS CONTEMPORARIES.' The impact of a meteor upon a vortex I suppose. Sir John states plainly here the reason for the . . . 'Appendix' .

In the days of the Vortex, before World War One, there was

No British Council

No Arts Council

No Courtauld Institute of Art Historians

No B.B.C. or Third Programme

No Television.

In 1912, in the place of this powerful mechanism for disseminating culture, we had to be content with the good services of Clive Bell and Roger Fry. At that time Art was a matter for artists mainly. What went on in their coteries, in the little galleries where they showed their work, even their manifestos – apart from certain 'Discerning Amateurs' – held little interest for the world at large. The curators, in the warm quietness of their galleries deserted of visitors, meditated among the pictures, or composed a monograph upon the Quattrocento.

Today, with two World Wars behind us, there has come a change. The large London Galleries, Provincial Galleries, Arts Council Galleries, overflow with enthusiastic throngs. Outside, the queues wait impatient for the glimpse of a Van Gogh. The curators are alert too. Private view follows private view in quick succession, punctuated by candle-lighted soirées, where 'ace' artists meet the cream of the collectors. Town-halls, once the abode of tax collectors only, have now their painting shows, concerts and poetry readings. Public gardens and the street corners too, are cluttered with the work of artists. As if this were not enough, they talk on the radio and perform on television. So it will be readily understood that in this era of intensive publicising and documenting of artists and their productions, how necessary it is that past art events should be correctly recorded. For instance, it would be easy, in the dim candle-light of a 'soirée', the atmosphere heavy with the perfume of cocktails, among a crush of patrons, artists, critics and art historians, for the 'Colleague' of 1914 to get mistaken for the 'Disciple' of 1956.

To judge from the Catalogue, something of this sort has actually occurred at the Tate. The Tate officials have, by the way Lewis's work is presented in the Gallery, as also in their lavish Catalogue, disturbed the balance of artistic power, as it were, that existed between the members of the Group in 1914.

The title of their Catalogue is 'Wyndham Lewis and Vorticism', but it is not the Lewis of 1914 who appears here, nor are the other artists the Vorticists of 1914 either. The Lewis here presented in 1956 is a giant swollen with fifty years' accumulated work, whilst the others, on their meagre twelve months' rations, are in contrast but skeletons of their true selves. This spectacle the Tate calls 'Wyndham Lewis and Vorticism', but this is no more Lewis and Vorticism than a picture of the Normans invading England in tanks would be of the battle of Hastings. Art historians, you have got your history wrong.

(Other Vorticists)

Having made a bundle of the former Vorticists – and some other artists who were not Vorticists – decorated with a strip of Lewis's Fade journalese, Sir John now attempts to throw them back again into that stagnant ditch Lewis calls a Vortex. But I do not think he will be able to lift it.

I had no wish to take part in a show of 'Wyndham Lewis and Vorticism'; it was not, I felt, a good arrangement for Vorticism. It should have been one or the other. Either an exhibition of Vorticism (in which case Lewis would have taken his place with the rest of us) or a retrospective show of Lewis only. No reply was returned by me to the Tate invitation, nor did I give permission for my work to be shown. During the exhibition I sent three letters to the Press expressing my reactions to the way the show had been organised. When they were not accepted, I issued them in the form of a pamphlet. That, I think, took care of the show.

The false position the Vorticists were forced to occupy vis à vis Lewis during the show will end when the show ends and the pictures are dispersed. However, there still remains the Catalogue. This florid coloured brochure fixes them indefinitely; it is intended to go bobbing, cork-like, upon the choppy seas of modern art, as its ancestor before it, for another forty years or more: unless something is done about it.

Vorticism for Lewis is everything he has ever done as an artist. Vorticism for the Tate is anything considered suitable to hang in the wake of Lewis for the purpose of this exhibition.

Vorticism for me is the work I did for the Doré Gallery exhibition, together with the drawings in the second Blast (War number) whilst a member of the Group. The painting 'Dancers', and the drawing 'Religion', reproduced in the 1914 Pink Blast, belong to my Pre-Vorticist period. These were done before I met Lewis. After we became acquainted he selected these two things for exhibition at his rebel Art Centre, later publishing them in Blast number one.

In 1917, whilst I was in France, Ezra Pound, acting on my behalf, sold my Doré Gallery pictures to an American collector, John Quinn. When I returned from the War, and began painting again, I gave up angular abstract designs, becoming more realistic in my War pictures done for the Canadian and British Governments.

The work shown in the Tate Exhibition was done during 1919–20, and is not Vorticist or abstract at all.

or

Les Disciples Malgré Eux

Sir John Rothenstein states in his Introduction that the 'Other Vorticists' are included to show Lewis's 'Impact' upon his contemporaries. Well, let us see. To speak of a Lewis 'Impact' in reference to the other artists included in the Catalogue is meaningless. Take David Bomberg, whose work is strong and individualistic, as a glance at his one exhibited drawing reveals. In his early years he drew inspiration from the French Cubists; had produced many fine Cubist compositions, notably 'The Mud Bath', long before Blast appeared. There is as little indication here of a Lewis 'Impact' as there is a Gauguin impact upon Renoir. The only impact noticeable in connection with Lewis and Bomberg is the impact of Paris Cubism on them both. The same is true of Edward Wadsworth and McKnight-Kauffer.

Wadsworth, whose relations with Lewis were closer than any other member of the Group, shows in his work not the least trace of an 'Impact'. Here again the influence comes from across the Channel; in his first phase Wadsworth has a closer affinity to Ferdinand Leger than to anyone else.

Then there is Jacob Kramer; nowhere is there evidence in his painting of a Lewisian 'Impact': the artist whose work interested Kramer most in his early years was Kandinsky, a man as different in his outlook from Lewis as chalk is from cheese. The preceding refutations are valid for both Frank Dobson and Frederick Etchells. With Etchells we might even find that Lewis was the recipient of a slight 'Impact'. To exhibit C. R. W. Nevinson here in this subordinate rôle is a joke that no one will relish more than Lewis, but to get an idea of what Nevinson's attitude would be if he could see himself in this setting, I suggest that the curious take a glance at his volume of reminiscences, Paint and Prejudice, where he mentions Lewis. With them it was a case of 'Impact v. Impact'.

Lawrence Atkinson is another independent artist whose eyes were too steadfastly fixed towards the Continent to be bothered by ' Impacts' at home. He had, moreover, aspirations to leadership of his own, and promoted a kind of rival abstract painting and music centre. Also the fact that he won a gold medal at the Venice International Exhibition, with his abstract painting, would strengthen his position as an independent. He is pressed in here, affixed with a combined 'Signed the Manifesto' and 'Invited to Exhibit' label.

Nobody, I am sure, after a study of the work of the principal artists listed here, would be able sincerely to speak of a Lewis 'Impact' upon them. This matter of an 'Impact' is merely to bolster up the Leader Legend. While denying an 'Impact', I am nevertheless prepared to agree that the authorities have well and truly 'Impacted' them in the rear section of their Catalogue. There is one artist, however, who has escaped 'Impaction'. Sir Jacob Epstein, although showing two drawings in the first Blast, is yet absent from the Show. Doubtless Sir John found it impossible to fit a Star of Sir Jacob's magnitude into the Tail of the Lewis Comet.

The Catalogue classifies the attendant artists into two sections, those who 'Signed the Manifesto' and those who were 'Invited to Exhibit'.

If anyone were to imagine we signed this Manifesto, pen in hand, in solemn assembly, they would be making a big mistake. I, in fact, personally signed nothing. The first knowledge I had of a Vorticist Manifesto's existence was when Lewis, one fine Sunday morning in the summer of 1914, knocked at my door and placed in my hands this chubby, rosy, problem-child Blast, the fruits of his own, Ezra Pound's and Nevinson's combined labours. For if the honour of christening the Group belongs to Pound, Nevinson in his book, Paint and Prejudice, asserts that he was the godfather of its offspring, Blast.

For several of the artists in the Catalogue, the only link connecting them with Vorticism is the ambiguous phrase 'Invited to Exhibit with the Vorticists of 1915'. To be invited to exhibit does not necessarily mean that one does exhibit. Atkinson, Bomberg, Kramer, Nevinson, were the invited guests.

A visit to the Tate or, what is more important, a perusal of the Catalogue, would lead the uninitiated to suppose that the artists designated as 'Other Vorticists' are in some way subservient to Lewis. Although this view might well suit some persons, to let it survive would not be just to the memory of such artists as Wadsworth, Gaudier-Brzeska, Atkinson and Nevinson, who, had they been living today, would have arranged this Catalogue differently.

'The Broken Vortex': the back cover of Vortex Pamphlet No. 2

Home page | Chronology | Bibliography | Collections | Exhibitions

News | Gallery | Auction results | The artist’s house | Contact

List of works illustrated on the site

Catalogue raisonné:

chronological | alphabetical